Guest post by Katherine Marshall, who will be one of the panelists at tomorrow’s webinar on ‘Emergent Agency in a time of Covid 19’ (register here)

Religious actors and transparency/accountability advocates ought to be natural allies, but all too often, they barely communicate, much less work actively together. That is a huge missed opportunity for both sides.

In the many ongoing discussions about post-COVID “building back better”, rebuilding trust, and strengthening alliances top many priority lists. Assuring efficient systems that deliver critical public health services, support vulnerable communities, respond creatively to massive education crises, assure financial systems, and the many other critical needs all confront wide and deep public skepticism about honest government, doubts shared by left and right, populists, radical reformers, and traditionalists.

The wide array of transnational integrity alliances (Transparency International is prominent among them) work to address these doubts. They keep corruption issues squarely on agendas, from the United Nations to country and local levels. They build on multi-sector alliances that include business, civil society, academia, and governments. They can show progress. But there is still a long way to go.

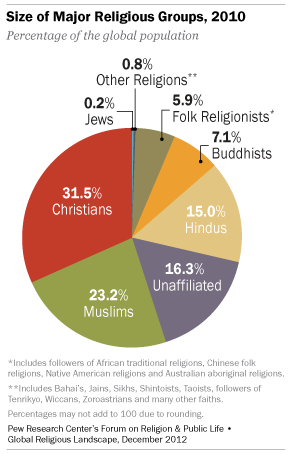

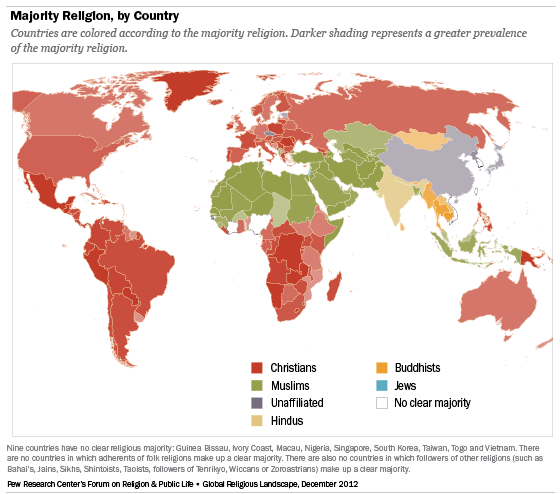

Where are the faith groups? Religious institutions, seemingly natural allies in the fight for integrity, are often strikingly absent in these efforts. That matters, not least because of their sheer size and reach: according to research by the Pew Research Center 84% of the world’s population have a religious affiliation and they are often more trusted than other communities, including governments and NGOs.

True, religious leaders speak out often about the evils of corruption and there are cases (Malawi, South Africa, for example) where courageous “speaking truth to power” has changed the game. But religious voices raised against corruption often fail to move from preaching to action, and they seldom join forces with anti-corruption activists.

The disjuncture of two large communities should matter to both, albeit in different ways in different places. To take some examples, corruption thrives in environments of religious and ethnic intolerance. Discrimination makes marginalized groups and individuals vulnerable to trafficking and other forms of criminal mistreatment. Corruption of various kinds protects those who promote intolerance, incite violence against marginalized religious groups, or profit politically and/or economically from such conduct.

Corruption undermines the protections that constitutions, laws, and international obligations provide for freedom of religion, belief, and conscience, freedom of expression, and protection from discrimination on legal grounds. Effective implementation and accountability (i.e. rule of law), is undermined by corruption and education curricula that are weak on tolerance and ethical values. Corrupt practices accentuate disparities in access to services and contribute to exclusion including by race and religious affiliation.

Religious actors can potentially enrich the work of corruption fighters and vice versa. With high levels of local trust and knowledge they can pinpoint and document the daily corrosive effects of corruption on poor communities. Individually and collectively, they can build on shared ethical teachings to bolster effective action. In contrast, their silence and acquiescence can abet corrupt actors, public and private.

Ways of working and thinking within both groups help to keep them apart.

Integrity alliances have tended to steer arguments towards technical approaches to fighting corruption, somewhat leery about an emphasis on morality and values as arguments for action. Views about religious communities can be colored by preconceptions that include religious ties to corrupt governments, ethical failings within religious communities themselves, and positions taken by more conservative groups on issues like LGBTQ and women’s rights. From the religious side, anti-corruption strategies can seem overly secular and technocratic. Arguments are often made that “it takes two to tango” with corruption charges weighted towards poor countries, while broader moral failings of global systems are obscured by a narrow focus on specific corrupt practices that lay most blame on those in poor countries.

But religious actors need to be an integral part of addressing corrupt practices within their own communities and beyond. They can contribute to efforts to address corruption on community, national, and global agendas. And religious actors, to move from preaching to impact, need the technical experience and tools that the integrity alliances have developed.

The issues involved are of course ferociously complex, with widely different communities and issues involved. Lumping all religious communities together distorts their wide diversity. Many religious communities have in fact developed practical steps to respond to corruption. And there is more openness among some integrity alliances to working together. But the overall picture is exemplified in the evolving program of the International Anti-Corruption Conference that meets next month , where not one proposal for a session came from a religious actor.

Used with permission from www.zapiro.com

For more Zapiro cartoons visit www.zapiro.com

What is needed are partnerships that offer broader tools and strategies to religious actors, and that open ways to recognize the links between ethical and human rights dimensions that soften the technocratic edges of anti-corruption rhetoric. Well-tuned, religious and non-religious groups can forge practical and meaningful links between human rights and accountability and integrity. Fighting corruption demands the engagement of all sectors of society, but with special applications for religious communities

Some specific actions can be taken, with the winds of the COVID-19 emergencies opening the way to new imperatives and alliances. Steps to promote common efforts include:

- Focus on specific topics linked to the COVID-19 emergency, notably proactive efforts to address both misinformation and knowledge gaps about vaccine testing, finance, and distribution. With deep mistrust in important communities, active religious engagement could be vital to success

- Common attention to accountability mechanisms both to monitor debt relief action and financial support for public health and support to vulnerable communities.

- Support for religious communities in developing accountability mechanisms appropriate to their needs and characteristics

- In select countries where anti-corruption strategies are under discussion, engage religious communities in the reflection and planning processes.

- Interreligious bodies can focus on understanding patterns of corruption, defining meaningful tools to combat them, and agreeing on specific priority areas for action.

With common, meaningful objectives and indicators of progress, religious communities can contribute more to broader community and national strategies, and integrity advocates can broaden their base and find new approaches and arguments.