Been reading some interesting (and challenging) reflections on protest movements recently, so the next two days will cover what I’ve learned. First up a Guardian ‘long read’ from Vincent Bevins, a journo, on ‘Why did the Street Movements of the 2010s fail’. The piece is based on his new book, If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution.

Although it’s written with verve, I wasn’t blown away by the piece – a bit meandering and too many generalizations, even by my standards. But the central argument, based on interviews with more than 200 participants in street movements across 12 countries, is worth taking seriously.

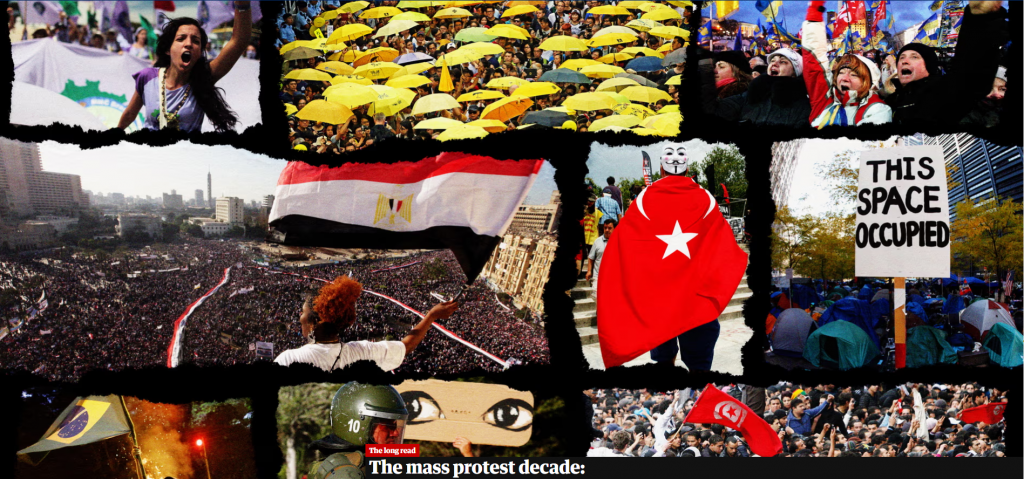

The set up: ‘In the decade from 2010 to 2020, humanity witnessed an explosion of mass protests that seemed to herald profound changes. These protests started in Tunisia and erupted across the Arab world, before huge demonstrations also rocked countries like Turkey, Brazil, Ukraine and Hong Kong. By the end of the decade, protests were roiling Sudan, Iraq, Algeria, Australia, France, Indonesia, much of Latin America, India, Lebanon and Haiti. During these 10 years, more people took part in street demonstrations than at any other point in human history.

Many of these protests were experienced as a euphoric victory by their participants and met with optimism in the international press. But years later, after most of the foreign reporters have gone, we can now see how the uprisings preceded – if not necessarily caused – outcomes that were very different from the goals of the protesters. Nowhere did things turn out as planned. In many cases, things got much worse.’

Strengths and Weaknesses: ‘The particular repertoire of contention that became very common from 2010 to 2020 – apparently spontaneous, digitally coordinated, horizontally organised, leaderless mass protests – did a very good job of blowing holes in social structures and creating political vacuums. But it was much less successful when it came to filling them. And there was always some force ready to step in. In Egypt, it was the military. In Bahrain, it was Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council. In Turkey it was Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In Hong Kong it was Beijing.

There was one kind of response that kept coming up [in his interviews, when he asked “If you could speak to a teenager somewhere around the world right now, someone who might be fighting to change history in some kind of political struggle, what would you tell them? What lessons did you learn?”]. I think Hossam Bahgat, an Egyptian human rights activist, put it best, or at least, the most directly: “Organise. Create an organised movement. And don’t be afraid of representation,” he told me without hesitation, in his office in Giza. “We thought representation was elitism, but actually it is the essence of democracy.”

I heard answers like this over and over, confirming research compiled by scholars. As early as 1975, the sociologist William Gamson found that movements succeed more often when they deploy hierarchical forms of organisation. In a wide-ranging 2022 study, the political scientist Mark Beissinger found that loose uprisings of the type seen in Ukraine’s Maidan protests of 2013 and 2014 tend to increase inequality and ethnic tensions, while they do not consolidate democracy or end corruption.

Not everyone I met had come round to favouring “verticalism” and hierarchy, and insisting that representation matters. Some people stayed in the same place. Mayara Vivian, [a Brazilian protester], remains mostly true to the ideals she adopted as a young punk. But in the years I spent doing interviews, not one person told me that they had become more horizontalist, or more anarchist, or more in favour of spontaneity and structurelessness. Everyone who moved did so in the same direction, closer to a classically “Leninist” view on how to organise political movements.’

And what’s happened to those activists since?

‘For some of them, the horrible comedown, the plunge into depression that came after things did not work out, was something like a hangover. You can get yourself all messed up on revolutionary elan, just like you can drink to excess or lose yourself in drugs. It warps your senses and causes you to make poor decisions. It isn’t real, and you’re going to pay for it later.

Then there was another interpretation, just as common. It is the most real thing that one can ever feel. It is not an illusion at all; it is a stunning, momentary glimpse of the way that life is really supposed to be. It is how we can feel every single day in a world when artificial distinctions and narrowly self-interested activities melt away. When our society truly is participatory, when we are truly forging history in every movement and acting in love and harmony with our fellow human beings, we will be able to feel this way all the time.’

Next up, activist guru Srjda Popovic and colleagues on what tactics work best in non-violent protest movements.

The bit about hierarchy in organisations really resonates. Movements are faced with a somewhat emotional dilemma: they often highlight how institutions and those in authority have misused and abused their power with devastating consequences, so its not surprising that they are often ambivalent about authority and hierarchy within their own movements. I guess authority is often conflated with authoritarianism and seen as something you can only misuse and abuse rather than something you can use for the good. One way of moving through this is for movement activists to take time to make sense and process. I write about this here: https://ajoydatta.substack.com/p/social-movements-what-lies-beneath. Maurice Mitchell writes about this and other dilemmas being faced by movements in the forge here: https://forgeorganizing.org/article/building-resilient-organizations

The hangover after the 2013 protests in Brazil hasn’t gone away. I was interviewed by a major newspaper a few months ago about the same subject. It’s a sore spot to say the least. And most scholars can’t make much sense of why and how it happened and why its results were so different that what most expected. I’m curious about the comparative analysis.

Thanks for these important reflections. I would also like to note the important contribution early on by Jo Freeman “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” which analyzes the challenges of street protests and direct actions which you can find on her webpage http://www.https.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny/htm This was written in 1970 based on the women’s movements, and sadly often quoted without attribution by others. Jo is a political scientist, author, scholar of social movements, lawyer and activist.

Historically, I don’t think it’s surprising that revolutionary movements and moments fail and, instead, lead to ascendance of reaction and authoritarianism. So this “failure” may look more like a normal pattern. But, it’s still worth exploring if the movements undermined their own effectiveness by, for example, rejecting traditional hierarchy and organizational models. I think a lot about the US Occupy movement, which I consider a failure. Given the attention and energy it inspired, I expected a lot more from it. But, like other popular movements, I think it was severely undermined by self-inflicted constraints. More generally, it was stymied by the reactionary (and racist) response to the Obama victory.

I should note that some friends and colleagues consider Occupy a success because it put economic inequality into popular and political discussion, highlighted the egregious inequality (99%).

It’s a valid argument, but I think the policy and economic impact has been very marginal.