‘Why are civil wars lasting longer?’ Asked a recent Economist essay – exactly the kind of big, hairy question to justify my subscription. Don’t agree with all of it, but very thought-provoking. Some extracts from a typically highly readable piece:

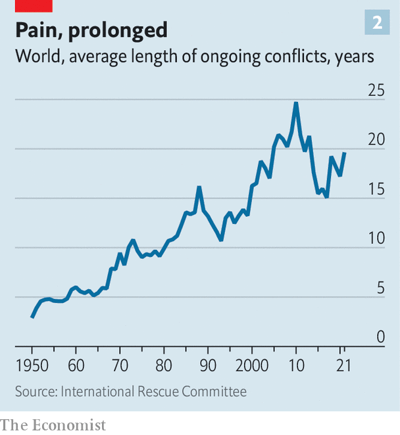

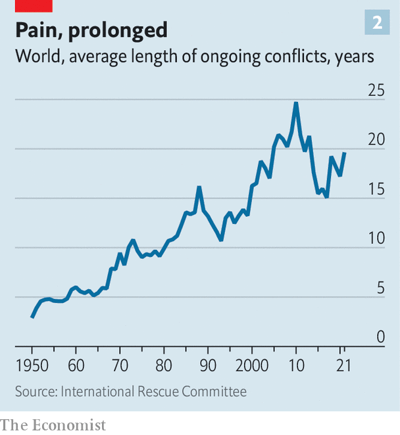

‘The average ongoing conflict in the mid-1980s had been blazing for about 13 years; by 2021 that figure had risen to 20.

[Why?] First, global norms are eroding. When Russia, a permanent member of the UN Security Council (UNSC), brazenly violated the UN’s founding charter by invading Ukraine, murdering civilians and kidnapping children, it showed how much taboos have weakened. When China, another permanent member of the UNSC, called Mr Putin a “dear friend” despite his indictment for war crimes, it confirmed that for some world powers, might makes right. This emboldens smaller bullies.Other factors are causing conflicts to burn for longer. Climate change is fuelling fights over water and land. Religious extremism is spreading. Organised criminals are making the world’s most unstable states even more so. And conflicts are growing more complex.

Complexity: Between 2001 and 2010 around five countries each year suffered more than one simultaneous war or insurgency. Now 15 do. Sudan has conflicts in the east, west and south. Complex wars are in general harder to end.

Civil wars are also becoming more international. In 1991 only 4% of them involved significant foreign forces. By 2021 that had risen 12-fold to 48%. Interventions by external powers with selfish agendas tend to make civil wars last longer and cost more lives. The costs for external actors are lower—their own cities are not being destroyed—so they have less incentive to make peace.

Climate Change: A review of 55 studies found that a one-standard-deviation increase in local temperature raises the chance of intergroup conflict by 11% compared with what it would have been at a more normal temperature.

Religious Extremism: Since the Arab spring, affiliates of al-Qaeda and (later) Islamic State have spread across the Middle East, Africa and beyond. They promise justice—such as the restoration of stolen grazing land—in countries where formal courts barely function. Once they have gained a foothold, they accelerate the collapse of state authority. The spread of jihadist groups makes it harder to end wars. Their demands are often impossible to meet, their foot-soldiers are fanatical, and external mediators hate dealing with terrorists.

Organised Crime: Civil wars in which a major rebel force earns money from illicit drugs or minerals tend to last longer. And the globalisation of crime has made it easier than ever before for such groups to get their hands on guns and cash.

Government forces are often greedy, too. Among the reasons why Congo’s war is self-perpetuating is that officers are paid a pittance but can make fortunes from embezzlement and extortion when deployed to combat zones. Locals complain about the “pompier-pyromane” (firefighter-pyromaniac) problem: regional strongmen who start a fire so the central government has to negotiate with them to put it out.

One country in Asia illustrates all the ills that make civil wars endure. Myanmar’s strife is staggeringly complex. Perhaps 200 armed groups control slices of territory or are fighting to overthrow the government. Some are armies seeking autonomy for large ethnic groups; others are local militias trying to defend a single village. The country has not had a conflict-free year since independence in 1948. Even compared with this violent past, though, norms have atrophied in the past two years.

Climate change is at work: the insurgency has gained strength in the central dry zone, which has been made poorer by drought. Crime, too, gives many fighters a reason to keep fighting. The army is deeply enmeshed in heroin and jade smuggling, as are some ethnic militias.

The world is not short of ideas for how to end wars. Find a respected mediator. Start unofficial talks long before the belligerents are prepared to meet publicly. Include more women and civil-society groups in the peace process. Accept that any peace deal is likely to be ugly. “Excluding people you don’t like from politics doesn’t work,” notes David Miliband, the head of the IRC. Purging the Iraqi army of all supporters of Saddam Hussein’s regime was a mistake, as was trying to build a system in Afghanistan without the Taliban. But the most important measures (build functional states in war-torn countries, curb climate change) could take decades to implement.

And global efforts to promote peace are hobbled by the fact that two veto-wielding members of the UNSC are serial human-rights abusers that object to interference in the internal affairs of blood-spattered regimes. Russia has used its UNSC veto 23 times in the past decade, scotching resolutions to allow more aid into Syria, investigate war crimes in the Balkans and (of course) to uphold Ukraine’s sovereignty. China has issued nine. America has issued three, mostly to protect Israel; France and Britain, none at all. In 2001-10, when Mr Putin’s imperial ambitions were more limited and Xi Jinping was not yet in power, Russia issued only four vetoes; China, two.’