It felt right that my last public gig with an Oxfam hat was to chair a panel at last week’s conference on Faith and Development (F&D), co-organized by Christian Aid and Islamic Relief. It’s one of this issues I’ve banged on about over the years, with limited (zero?) impact on the determinedly secular world of aid.

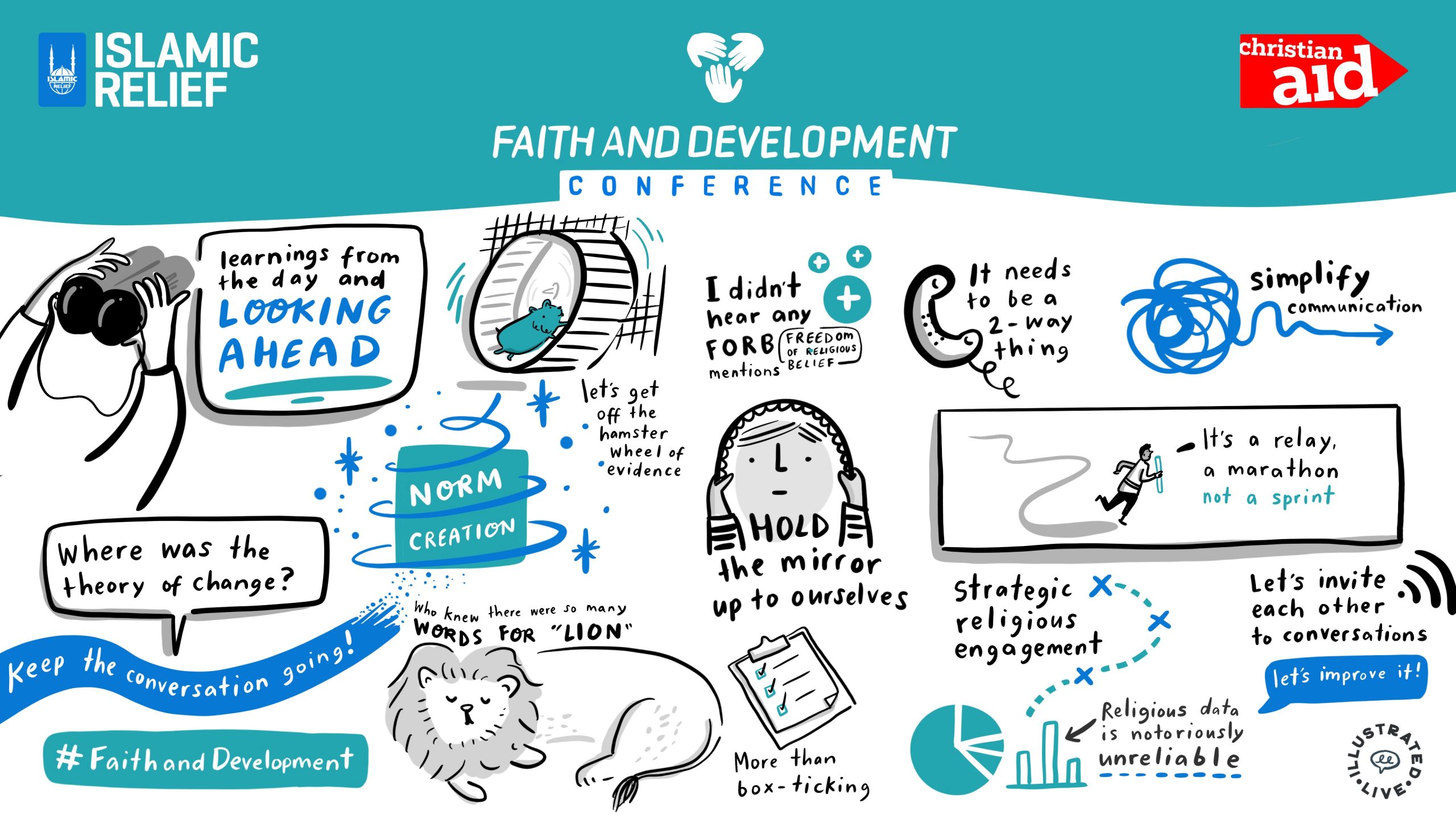

There was a live illustrator – here’s her version of the panel I chaired. Any guesses which bits came from me?

Illustration by Katie Chappell at Illustrated Live katiechappell.com

“Short version: if you care about people living in poverty– what motivates them (agency), who they trust, how they organize, in many countries faith should be your starting point. Quote from a Zimbabwean theologian (Sophia Chirongoma): ‘75% of Africans profess a religion: life is religion, and religion is life’. Yet when I asked our Oxfam staff in DRC if they worked with the Catholic Church (probably the closest thing to a truly national institution in that country), the reply was ‘sure – we get them to hand out our leaflets’.

For a devout atheist like me, it was fascinating – shame the conference was almost entirely made up of people of faith (I checked), because the rest of the largely secular aid world could have learned a lot. In some areas Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) seem to be way ahead. Some examples:

The power of money: If there’s one thing FBOs know about it’s raising cash from believers. I’ve written before about the phenomenal potential of zakat (Muslim wealth tax, usually linked to Ramadan), but here I learned about waqf, another channel for donations linked to Islam that is both booming and evolving. These local fund raising mechanisms (and there are plenty of equivalents in other faiths) create a genuine alternative to aid dependence – who needs to jump through aid agency hoops when the money can be raised locally? (See also my usual Fundraisers Without Borders rant – people I spoke to at the conference thought this would be a great contribution.)

Localization: Faith actors are ‘the software of localization’ (Waseem Ahmad, CEO of Islamic Relief). Centuries of fund raising has built an unparalleled social network, which can be used as a source of understanding + safety net in humanitarian response (Ebola, Covid etc) or to genuinely localize other areas, via community care of the elderly or religious teachings that build resilience (both through personal stoicism and caring for your neighbours).

Norms: Christian Aid CEO Patrick Watt channelled Amartya Sen, describing the true nature of development as ‘being more, rather than having more’. Over the last 20 years, I’ve seen work on norms move up the aid agenda – on rights, consumption, citizenship, but the proponents have relied largely on the great work of feminism for lessons and ideas, ignoring the centuries of normative work by FBOs.

That last point is the one usually referenced by secular aidies as an ‘ick factor’ that prevents them engaging with faith. As Massimiliano Sani of UNICEF pointed out, 20% of child marriages in Malawi are officiated by Church leaders. So yes, faith can be part of the problem, but so can governments, and that doesn’t prevent us engaging with them. There were insights on the ability to shift norms within FBOs through the reinterpretation of scripture. That reminded me of conversations with Islamic feminists in Mindanao, who had done exactly that.

The key in all this is faith literacy – get to know your faith actors, find out who thinks and believes what, identify areas of cooperation. Getting inside the Catholic Church during my years at CAFOD revealed an institution full of diversity and conflict – plenty of opportunities for good guys to make alliances, and take on the other kind.

But the conference also added an extra layer to this. Just as my LSE colleagues are urging the aid world to broaden its understanding of ‘public authority’ to give more weight to customary law and traditional leaders, the faith activists see the need to understand and incorporate unusual suspects – both the new Christian Churches, like the evangelicals and pre-colonial faiths that are often still important in people’s lives.

Working with faith actors on norms is all the more pressing because of the backlash against what one speaker called ‘that stuff’ – norm changes that are seen as coming from outside, imposed by foreigners.

So why has so little changed? The ‘turn to religion’ in the aid sector is so far still largely instrumental – things like getting faith organisations to push the SDGs (back to those leaflets in the DRC). But as Amjad Mohamed-Saleem of the IFRC said, ‘we cannot just be invited for breakfast prayers; we have to be at the table’.

But I found the discussion on how to move things forward a bit paradoxical. After stressing the importance of valuing other kinds of knowledge, not just the purely Western rational variety, this group seemed to have few ideas beyond ‘chuck more evidence at the seculars’. But we have an abundance of such evidence, and it hasn’t had much impact. I ended up (as I usually do) asking ‘where’s your theory of change?’ How do you convert a good understanding of where the aid sector is at into a strategy for influencing it? Things like shaping narratives, finding the right messengers and moments.

Finally, faith organizations’ reach is pretty impressive in the rich world too, despite claims of secularization. UK Development Minister Andrew Mitchell read out a greeting from King Charles on the importance of faith to development that was more like an essay (and a rather good one). Mitchell himself then spoke, and a handful of FCDO types attended throughout the day.

I hope there will be more than 2 agnostics and 3 atheists (including me) at the next such discussion – it’s really important.

You are so right to keep banging this drum, Duncan, despite all the complexities. Knee-jerk negativity towards potentially valuable allies still sadly pops up from time to time.

Author

Thanks Julian, somehow as an atheist, it seems less personally compromising, so I’ll keep on banging!

Ian Scoones has done good work in Zimbabwe on the intersections between rural livelihoods and religion- there’s a series of three blogs which start here.

https://zimbabweland.wordpress.com/2022/11/21/religion-and-agriculture-reflections-from-zimbabwe/

Keep rattling the cages, Duncan. Here in the west we regard lack of religion as nothing unusual (another example of projecting our values externally), but in the developing world most people regard the absence of religious belief as mystifying. Faith-based groups operating on the ground within local communities will always be more effective than a bunch of western suits interested only in what they can measure. A lot of priests or imams have degrees of credibility aid workers could only dream of. If they will endorse what is happening, it makes progress so much easier.

Faith-based aid workers are also really great value for money!

Interesting discussion and blog – also reminds me of the potential described by Faith Invest and Al-Mizan for faith organisations to work collectively to really transform investment and financial markets from profit-led (including arms, fossil fuels, etc) to values led propositions for peaceful and sustainable development.

At Misean Cara in Ireland, but with faith-based member organisations working on sustainable development globally, we tried to advance discussions on appraising & valuing the contribution in the GEM Report 2021: https://www.miseancara.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MC-Policy-Briefing-_-Valuing-FBOs-in-Education-_-Final-_-29-04-21.pdf

Misean Cara also has a discussion paper (and operational practice) on efforts to really integrate a focus on the ‘Furthest Behind First’ throughout the life cycle of our members’ faith-based development work. We have not seem much out there, in practical terms, on how to focus on Furthest Behind cohorts in development practice from mainstream and secular development actors – apart from the UNDP, operating at a different level – so hopefully it may help to move that discussion along a wee bit.

We’re always looking to at ways to capture the leveraging of ODA funding with local and international funding brought to bear on initiatives; and the possibilities to leverage progressive, systemic change for people, planet and peace through faith organisations’ presence and work within international forums – on development, humanitarian, climate action, human rights, debt, financing for development, etc.

Always looking forward to continuation of the discussion, and I appreciate that you – as an affirmed atheist – remain open to critically considering the pros and cons of faith organisations in development.

Good luck with the next stage of your life in academia, and look forward to seeing how and where the continued blogging will land…

Author

Thanks Eamonn

More than just faith, it is the inner character of individuals, their backgorunds, quality of interactions with others, amenability and interest in listening, particular skills for the work, understanding of and compatibility with a culture that contribute to meaningful efforts.

I have worked with or interacted with various Christian denominations, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish groups, as well as atheist or simply non-denominational secularists and have found as many ineffective, disinterested, myopic individuals in religious organizations as in non-religious ones.

A meticulously prepared meeting, trying to dig into some of the live issues that help explain Duncan’s listing of the “faith dimension” as a “miss” and frustration that something so obvious continues to limp forward, then back. Duncan’s final panel surfaced lots of challenges (several of mine are on the illustration). Time to move ahead.

Thank you, Duncan, great insights. It’s a small world, this “religion and development” space, and it’s in need of these types of reminders: where is the theory of change?? What is the strategy beyond just “more evidence”?? There are some examples, such as the Journey of Change with the UNICEF program (pg 19 onwards here: https://jliflc.com/resources/unicef-global-programme-guidance-on-faith-engagement/), but we need a bigger picture for this field as a whole and that needs work. There’s some hope with “strategic religious engagement” and we’ll see where that takes us…

What about the faith-actors guide to non-faith engagement? Faith actors are the ones with much of the realised local engagement, theories of change that relate to people and not programs outputs and outcomes, and real social and spiritual capital. Let’s turn the table and look at this debate from the viewpoint of the faith-actor, rather than the current dominant discourse.

I was on a panel yesterday in a WHO webinar on “Community Protection Partners Meeting: communities at the centre of managing health emergencies” – the only one formally wearing the faith hat out of over a dozen speakers. Among others i mentioned the need for “faith literacy among health leaders”, just as most are so sold over “health literacy among faith leaders”

Author

Nice, Mwai – hope they heard you!