ALNAP, which describes itself as a ‘a global network dedicated to learning how to improve response to humanitarian crises’, has just published a really good series of ‘essential briefings for humanitarian decision makers’. Proper grown-up sitreps, full of difficult questions with no easy answers (and quite a few unexplained acronyms, which can make them a bit inaccessible).

The one that jumped out to me was the paper on localization, maybe because I’m more familiar with those debates. The other updates are on the humanitarian-development-peace nexus, the climate crisis and humanitarian action and accountability to affected populations. Each one comes as a factsheet, a shorter two pager, and the full 4-6 page briefing, though you’ll have to hunt around on the website a bit to find them all.

Some highlights from the localization briefing:

‘There is still little generalisable and empirical evidence pointing to how to shift the system to be more locally led. The humanitarian sector is still unclear, and has yet to develop consistent analysis and understanding about the intended outcomes and the ultimate impacts of localisation.

Direct, quality funding flows to local and national organisations is still the primary way the system measures progress on localisation commitments.

Despite some smaller agencies and donors revising partnership policies and practices to be more favourable to local organisations, direct funding flows to them remain a small fraction of aid financing, varying between 1.2% to 3.3% of all funding over 2018-21.

COVID-19 didn’t prove to be the tipping point it could have been in getting money in the hands of local partners. While local and national organisations were at the forefront of delivering the response, just 2% of the funding went directly to them.

Ukraine is a textbook case of the unfulfilled promises of localisation. Local and national organisations had received only around 1% of direct humanitarian funding by the anniversary of the Russian invasion, but are shouldering the most risk and burden of compliance requirements.

A handful of donors, UN agencies, INGOs and the IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) agreed to develop individual roadmaps with milestones to reach 25% funding to local organisations. These are set to be published by the end of 2023.

‘local and national organisations were present in 80% of Humanitarian Country Teams (HCTs), but accounted for only 9% of the HCT leadership’

Country-based pool funds (CBPF) have been the most effective means of getting funding directly to local actors while also managing the risk concerns of international groups.

In 2022, 27% of the global CBPF fund went directly to local and national actors.

The country-based pooled fund in Ukraine, partly made up for the low direct funding to national NGOs there. Now the world’s largest CBPF at $327 million, it doubled its allocation to local organisations to 33% at the end of 2022.

But UN CBPFs make up only 10% of overall humanitarian funding and exist in less than half of countries with humanitarian response plans.

Several pool fund models exist, including those managed by the NEAR Network, START fund and FCDO/Danish Refugee Council, which prioritise funding to local partners and have built-in flexibility that UN-led funds don’t always have.

When it comes to quality, long-term, flexible funding, agencies are at various stages of progress. The common subcontracting model means local groups hold most of the risk responsibility but don’t have the funding to cover basic administrative costs.

Indirect cost recovery (ICR) or overhead costs continue to be a stumbling block to quality funding. According to recent research by Development Initiatives, there is no standardised ICR policy across the sector – some split these costs with local partners equally, others provide a set percentage, while others give a proportional or even negotiated share.

Typically ICR provisions stop at the first level intermediary, without reaching smaller local actors implementing on the ground.

For recent crises like Ukraine, organisations have put forward a number of equitable partnership draft proposals which call for, among other things, mandating fair overhead cost recovery for all subgrantees.

Some big donors are making changes to policies and practices that could push through greater change.

The US has taken a vocal and leading role, committing to giving 50% of all funding to programmes which ‘place local communities in the lead’ by 2030. To date, 10.5% of their funding goes directly to national and local organisations. While ahead of the rest of the sector, this is still far from their 25% commitment by 2025.

The EU has followed, with Guidance in March 2023 focusing on Promoting Equitable Partnerships with local responders in humanitarian settings.

[But] In Ukraine, neither USAID nor the Directorate General of ECHO have provided direct grants to national NGOs.Many other donors are in the process of inspecting and changing their grant-making models to align with the localisation agenda.

Donor caution around risk drives much of the hesitancy around funding for localisation. Yet donors and intermediaries have yet to fund appropriate risk mitigation measures.

Overhead costs such as security and financial management to mitigate fiduciary risks have not been supported to the extent that they would meet risk thresholds of many donors.

Risk-sharing models are being piloted, most recently in Ukraine. These include agreeing to acceptable levels of residual risk between locals and internationals, with positive benefits.

The literature predominantly focuses on the risks to international actors when partnering with local actors, rather than vice versa, raising issues of power imbalances.

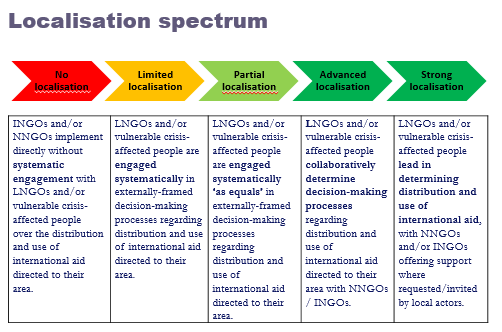

While local organisations are increasingly present in the formal coordination system, the decision-making and leadership roles remain dominated by international perspectives, leading some to question whether the inclusion is tokenistic.

A 2021 IASC mapping of more than 2,400 coordination structures in 29 humanitarian operations found local and national organisations were present in 80% of Humanitarian Country Teams (HCTs), but accounted for only 9% of the HCT leadership.

‘Lingering Questions’ include:

Is localisation about equity or effectiveness? Much of the literature promotes localisation not only as a way to address the power imbalances within aid, but also as a way towards a more relevant, timely and more cost effective response. The literature also points to localisation delivering greater resilience, sustainability and links with development – improved accountability to affected people. However, current evidence to back these assumptions is weak.

Government role in localising responses? A more locally-led approach depends on strong and open civil society. But across the world, civic space – seen as the right to peaceful assembly, association and expression – is in decline, even in countries with long democratic traditions. Repressive, corrupt and/or weak government structures may limit the humanitarian space for both local and international actors.’

Really good stuff.