Exfamer Erinch Sahan reflects on his first 100 days as boss of the World Fair Trade Organization

100 days ago. I left Oxfam to lead the World Fair Trade Organization. After seven years in Oxfam I had got hooked on one specific question: ‘are business structures that maximise power and returns for investors the only viable option?’ So now I lead a network of over 300 Fair Trade social enterprises that aim to show that business can indeed pursue a social mission. Today is my 100th day as the chief executive of the World Fair Trade Organization and it’s time to reflect on where I now stand on what businesses can and should become.

Which matters more, business structures or people?

I spent years arguing that it’s about business structure, stupid. The words of the late Pamela Hartigan rung in my ear: “The key to sustainable capitalism is reasonable profits as opposed to maximizing profits.” But if a business is structured so it must always make decisions that maximise profits, then that business is in a straitjacket. And I spent years trying to capture which structural features characterise this neoliberal straitjacket, in reports like this one with the Donor Committee on Enterprise Development and our framework in the recent paper on Fair Value developed with Oxfam policy-wiz Alex Maitland.

I still think structure is critical – an enabler and an indicator of a business that is focused on more than just profits. I still tout the employee-ownership models of WFTO members like Creative Handicrafts or the almost text-book example of the multi-stakeholder governance model of El Puente (producers, workers, customers and founders have equal share and power).

But since taking on my new gig I now see that the story is not so clear for smaller businesses. I’ve already met dozens of business people from across our membership – social entrepreneurs who lead successful mission-led enterprises through a variety of structures. All members have the requirement of having their social mission in their key governance documents – that’s standard (alongside a long audited list of requirements).

But it’s the priorities of the individuals leading the enterprise that are often what really makes them mission-led models of business. It’s important that structure shouldn’t inhibit this (as having impatient investors dominating the board would) but structure isn’t the only feature driving decisions in small business. I now feel that business structure becomes relatively more important as a business grows.

Businesses that will stick with their suppliers, through thick and thin

I look at businesses and I now see a dividing line I didn’t see before. I see businesses who are non-committal to their suppliers (e.g most big food brands who buy through commodity markets) and those who are truly dependent on their suppliers. This matters, because if your brand or supply chain model is inherently linked to a group of farmers

or a community, you cannot just up and leave when you find a cheaper supplier. You have to support your suppliers to improve, pay them enough to be sustainable, use your voice in favour of the community’s interest. I’m now meeting more of these businesses that were deliberately set up to work with local suppliers – businesses like Sasha in India, Turqle in South Africa, Calypso in Chile or Selyn in Sri Lanka (all WFTO members) who have built business models where they cannot simply abandon their producers if they find a cheaper option. Examples like Village Works in Cambodia, who produce the official Fair Trade Tartan is also fully embedded in its community. Assessing this is possible and is part of the WFTO Guarantee System before any business becomes a WFTO member.

Profit maximising companies-like Adidas and Nike will shut down factories when there’s a cost saving to be enjoyed (if currency markets shift, governments raise costs through higher taxes or minimum wages, or a new cheaper supplier pops up anywhere in the world). This flexibility is built into their model and means they aren’t ever in a long-term partnership with the people who make their products. Stuck in the constant pursuit of ever-higher profits, Nike is looking at labour cost reductions of around 50 per cent for some shoes, leading to a bump in margins and happier investors.

That’s the way shareholder capitalism is designed, but we have a choice in shaping the kind of businesses that populate our economies. Instead, we should celebrate businesses who are fully embedded in their community, ready to stick with them through thick and thin.

But I still think business structure is central if we want to tackle inequality

The business world is diverse, but in most countries it is dominated by businesses that exist primarily to grow the capital of their investors. This is especially the case for larger companies. Profit maximisation does have incidental positive impacts: it drives investment and leads to innovation.

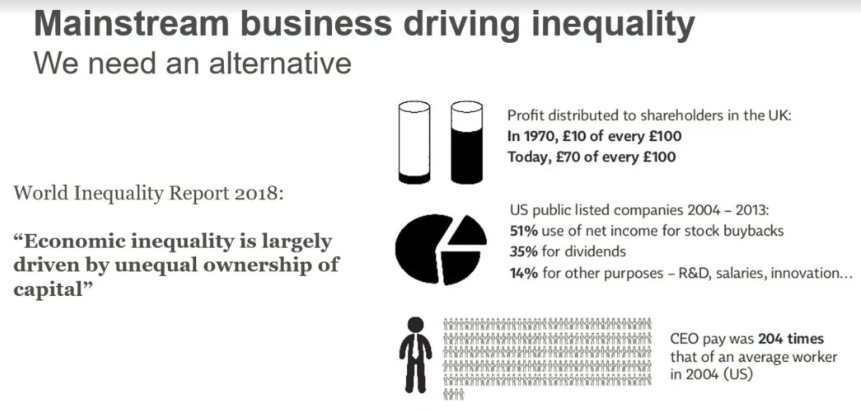

But it also means that business is geared to extract as much value as possible, and distribute this value proportionately to people based on the capital they have to invest. In a world where unequal distribution of capital is the key driver of inequality (according to the World Inequality Report), this essentially supercharges business to drive up inequality. While anyone can be a shareholder (through a pension fund for instance), if economic spoils are shared according to the size of capital people had to begin with, we give a growing share of the pie to the people who have the most to invest. Laws, financial markets and industry policies have made this the dominant model in many countries. But it contains a fatal design flaw if we don’t want to see spiralling inequality.