Abby Stoddard, Paul Harvey and Tonia Thomas present new research from Humanitarian Outcomes, supported by the UK Humanitarian Innovation Hub (UKHIH). Full report here.

Over 100 days have passed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine sparked a massive humanitarian crisis along with an outpouring of international generosity in the form of aid contributions. So why are international organisations still sitting on millions they cannot spend while local volunteer groups in Ukraine are reaching their limits, emotionally burned out, and running out of cash and equipment?

Our consultations with over 60 representatives from a range of national and international organisations show that, although Ukraine is an atypical humanitarian crisis for the international humanitarian system, it has responded with typical approaches. The results have so far been deeply disappointing.

The Ukraine crisis is the product of an old-fashioned international war, and an example of what humanitarians term a “massive, sudden-onset emergency,” more often the result of a natural disaster. The international agencies were not able to immediately deploy and scale-up aid operations because of the dangers involved in operating in active conflict, and even those that were already working in Ukraine since the 2014 crisis did not have contingency plans ready for a full-scale invasion.

When all aid is local, but “localisation” is nowhere to be seen

The first responders in crises are always neighbours and local bodies. In fact, the idea for the Red Cross was born when Henry Dunant witnessed the valiant but completely overwhelmed efforts of local volunteers in the aftermath of the 1859 Battle of Solferino and thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if these folks could be properly resourced and organized?’

The response in Ukraine is no different, and in the first days and weeks after the invasion, the aid that people received was overwhelmingly provided locally. In addition to local government and community organisations, small groups of volunteers began to form—ordinary people pooling their resources and responding to requests for help in their area. Six weeks in, while most international agencies were still starting up or sending assessment teams, there were an estimated 8,500 small volunteer groups and around 2,000 Ukrainian NGOs and CSOs (including 1,700 new ones, in the process of registering).

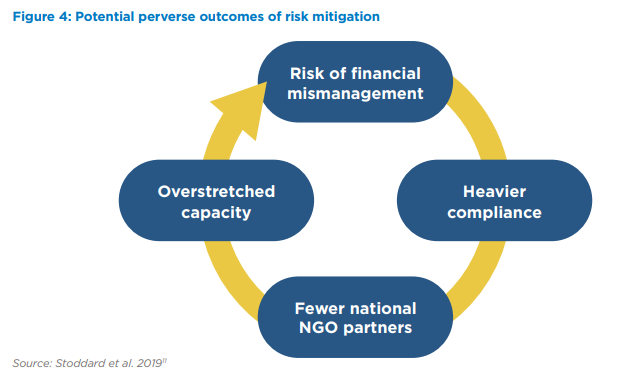

But the international humanitarian system in 2022 is not structured in a way that allows for rapid infusion of money and materials to local aid groups. Instead, the international agencies have held back their funding while they did their required due diligence. Their donors and internal compliance frameworks have insisted they can only fund local partners that have demonstrated capacity and organisational and fiduciary mechanisms that meet certain accountability standards—in short, which look more like them, only smaller. Unfortunately, there were only a couple of hundred such organisations in Ukraine that fit that mould prior to the current crisis, and they can’t be everywhere or serve as the funnel for everyone.

Since 2016, the international aid community has committed to the Grand Bargain agreement to “localise aid,” which includes the goal of providing 25% of humanitarian funding to local actors “as directly as possible.” As of May 20th, local organisations in Ukraine had received less than 0.1% of direct funding, and pass-through funding contracts were being held up by lengthy application and vetting requirements. Hence the startling conclusion of the report that, “The groups that are actively scaling up and becoming registered as new aid organisations have done so by finding donors mostly from outside the formal humanitarian sector.” In other words, their support has come from individuals and organisations evidently not subject to the same rigid compliance frameworks that have hamstrung the humanitarian agencies, supposedly in the business of rapid response.

This damning situation is not lost on the international aid workers. Many of those consulted during the research for the report expressed intense frustration at their dilemma. In the words of one international NGO team leader in Lviv, “We KNOW that in sudden-onset crises it is neighbours and friends who respond. This is what we should be telling our supporters, this is what the value of partnership is…We could have funded and facilitated the funding of these spontaneous groups instead of them having to spend their own money.”

Cash to the rescue?

OK, so if the well-funded international organisations and donors can’t find a way to provide support to the Ukrainian groups helping civilians in the embattled areas in the east, they can at least pump money into cash assistance that will reach displaced people and others in need in the rest of the country, right? After all, Ukraine is a developed European country with functioning markets and banks, and good digital connectivity. What’s more, the government already has a social cash assistance mechanism that could, in principle, be expanded to reach all Ukrainians who suddenly need it.

Not so fast. The agencies and government have struggled to agree on criteria for selecting beneficiaries, or a suitable process for sharing information in a way that protects data privacy. As a result, rather than a single pipeline that could be topped up by international contributions, no fewer than seven separate mechanisms have been set up, with agencies identifying their own beneficiaries according to their programmatic focus. And of course, each pipeline takes time to start flowing. One INGO was fielding calls from families who had registered for another agency’s cash program and two months later had still not received anything. When the INGO asked if they could distribute cash to these people in the interim, they were told “No, these are our beneficiaries.”

Course correction is possible

International humanitarians have long been their own harshest critics and have used previous failures as learning opportunities to reform the sector. The same can be true for Ukraine. International entities could start by adopting more flexible guidelines for funding local aid actors that are appropriate to the situation and the level of need. The more urgent the need, the more the emphasis must be on speed and reach, dispensing with dilatory administrative measures, at least in the short term. Agencies and their government donors must understand and accept that this comes with an inevitable risk of losses and mismanagement—and that the risk is worth it.

Changes like this could go a long way toward improving the reputation of international aid groups among the Ukrainian public, which has rightly suffered.

This is important because, for all its dysfunctions, an international humanitarian presence is needed in Ukraine—as witnessed in the ICRC’s evacuations of civilians from Sumy and Mariupol. In the pessimistic but plausible scenario that recent Russian gains continue, and the country becomes mired in protracted conflict, the need for international actors to negotiate humanitarian access and to facilitate cross-line and cross-border operations will increase. In view of this, international humanitarian actors should focus now on two broad objectives:

1) supporting and complementing Ukrainian efforts in government-controlled areas, and

2) devising ways to reach civilians in territories held by the Russian military.

In doing so, they will have to engage much better with local aid groups – as partners, not as compliance officers.

To continue the conversation, please join our event on 5th July