Local actors can deliver programming that is up to 32% more cost-efficient than international ones, one study suggests. Yet, particularly in fragile contexts and conflict zones, international actors still seem reluctant to localise. Economist Sophie Pongracz looks at cash transfers to explain why it’s time for the humanitarian sector to take a proper look at the evidence on cost-effectiveness.

I was of one the economists talking about the efficiency/value for money of localisation that Duncan mentioned in his recent blog. Since then, I have also led a session on value for money or cost-effectiveness (as the Americans call it) at the Forum on Social Protection in Fragility and Conflict in Rome in mid-October.

Both sessions were timely as USAID has just published a position paper on cost-effectiveness and a position paper on direct monetary transfers. Tom Fletcher, new Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator (the UN’s top humanitarian official), has also said that he will “battle to make us more efficient, strategic, inclusive and innovative”.

Here, I want to look specifically at the cost-efficiency and cost-effectiveness of social and humanitarian cash transfers in fragile and conflict affected places. Because in these places in particular, international actors too often make strong assumptions about what works and what does not without taking into account evidence on cost-effectiveness, what drives costs in programming and risk levels. Key assumptions include that:

- cash is risky to deliver and will get more easily diverted than in-kind aid;

- only ‘neutral’ humanitarian actors can deliver despite evidence to the contrary; and

- in crises they cannot use national or local systems to support the most vulnerable, and that only an international parallel UN system can take the risks involved to deliver the response needed.

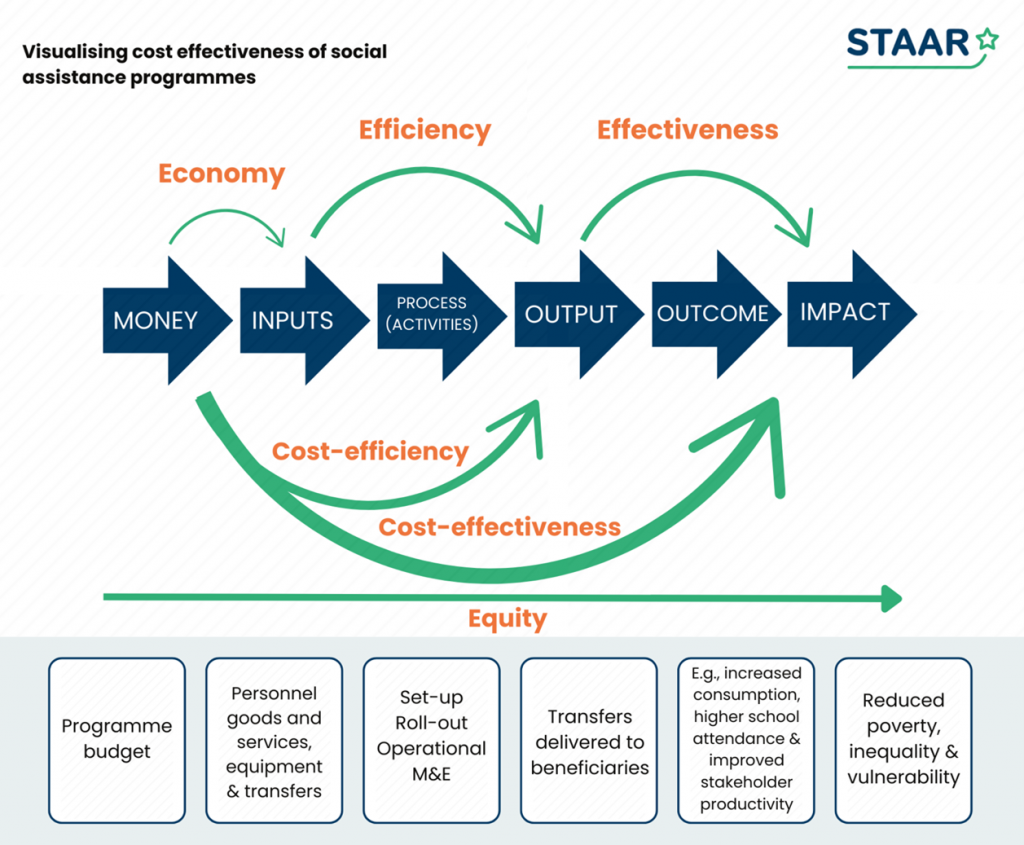

Before throwing numbers at you, I wanted to show visually what cost-effectiveness is. The graph below relates to monetary transfers (or cash transfers or social assistance transfers). It is adapted from the UK FCDO’s Value for Money approach.

Making the biggest impact with what you have

The most important point to understand about cost-effectiveness is that it is not about reducing budgets. It is about making the most with the resources you have to maximise the outcomes for the most vulnerable. So, here are some numbers to make the point:

A recent seminal study by The Share Trust found that local actors could deliver programming that is up to 32% more cost-efficient than international actors. Translated into the delivery of scarce resources on the ground, the implications are significant. For example:

- In Ukraine, if 25% of 2023/24 humanitarian assistance had been channelled via local actors, estimated cost efficiencies would have been $256m.

- In a country in the Middle East, 1.1 million more people could receive cash in one year if funding went directly to local actors.

The data from cash programming is equally eye-catching:

- Cash is often as much as 2-3 times cheaper to deliver than food aid, and generates significant benefits to the local economy. But in Ukraine the share of in-kind assistance and services (ie stuff that is much less cost effective than cash) increased from approximately 68% to 78% from 2023 to 2024.

The problem of duplication

A big source of inefficiency is when international actors set up parallel and uncoordinated systems in conflict-affected areas, even when development systems and social registers already exist. That leaves a major need to de-duplicate so the same people don’t get assistance from several different humanitarian actors. For instance, in Ukraine, from February 2022 to September 2023, removing such duplication saved $163.2 million and allowed higher coverage of persons in need.

Amid increasing humanitarian need and limited resources, we need to pay attention to the evidence that national and local systems can be used in crises; that local government and non-governmental actors are usually the first responders in settings that international aid cannot reach or is slow to reach; and that the evidence on the preference for, and cost-effectiveness of, cash is loud and clear.

Six key questions for those seeking better value for money are:

- What keeps us from starting with the national and local systems and actors that are already there?

- Why are parallel systems set up despite them probably being less efficient, less effective and definitely not sustainable in many contexts?

- Why are donors not asking for/not receiving budgets from UN agencies in a transparent and disaggregated manner to carry out efficiency and cost-effectiveness analysis?

- What myths need busting around perceptions of risks? Why is the evidence not followed? Why is cash still not the default?

- Why are we thinking about the costs of inclusion but not the costs of exclusion?

- And what could we immediately change at country level to become more cost-effective in the interests of the most vulnerable populations?

My thinking on these has been helped by intensive discussions at last month’s Forum on Social Protection in Fragility and Conflict, which resulted in an unofficial Charter for Action (see the end of this Forum Report) that included cost-effectiveness.

It’s clear that real progress will require substantial changes in incentives and power structures. The FCDO is setting up a High Level Panel on this for that purpose.

But here, I just want to highlight a few practical ideas on what we, at the technical level, can all do differently from tomorrow to start bringing cost-effectiveness thinking into decision making in crisis response:

On cost:

- Inform ourselves about the costs of different options for modalities, actors and systems of delivery. When considering working through an intermediary, be clear what the costs and the value/benefits are.

- Consider the costs of exclusion not just the costs of inclusion (this is particularly important, cost-effectiveness is NOT about leaving out the most excluded because they are costlier to reach – in fact being effective means doing the opposite!).

- Ask questions about why overheads are not being passed on to local actors.

On effectiveness:

- Inform ourselves about what existing national and local systems exist and deliver.

- Map the local ecosystem of formal and informal social assistance actors and ask them what functions they can and want to fulfil.

- Ask for and share evidence on the effectiveness of different approaches.

On risk:

- Share risk assessments.

- Disaggregate risk categories and be clear what risks you are talking about when planning how to manage them.

- Make the case to take calculated risks for higher benefits when contributing to funding decisions.

These are steps everyone can take forward right now, whether we work in governments, in donors, in UN agencies or in NGOs. It’s time for all of us to stop talking and start acting.

Sophie Pongracz, is currently the technical lead of the STAAR facility. She previously spent 20 years at the UK’s Department for International Development (now the FCDO) as an economist working on fragile states and humanitarian aid.

Hi there. this aligns very much with this video put out by the CALP Network earlier this week. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/calp-network_the-case-for-local-solutions-to-global-crises-activity-7272622565653635072-xldF/

This is such a helpful and interesting article, Sophie and a great read. It points to how much of the current ways of working in the sector that deny power and resources to local actors are not based on any evidence at all. This makes the data you have put together provide such a powerful argument for transformation.

That Value For Money arguments support all the other arguments for locally led development is valuable but I would be curious to know whether you see any danger in donors only looking at this? Without a wide definition of Equity, might there be situations where necessary higher costs of locally-led development around flexible funding, capacity development, network building etc would be excluded under VFM? Or do you think that once donors accept that local and national systems are the places to start, this becomes less of a problem, particularly if they focus on the cost of exclusion?

Excellent article Sophie – love how clearly you set it out. I attended a convening on locally-led climate adaptation and much of what I heard reaffirms the key points you have made here.