Sat on a panel on localization last week in a meeting of aid economists (no more detail, sorry – Chatham House Rule). It was definitely a different tone to the usual conversation on localization, which concentrates on issues of power, equity, decolonization etc.

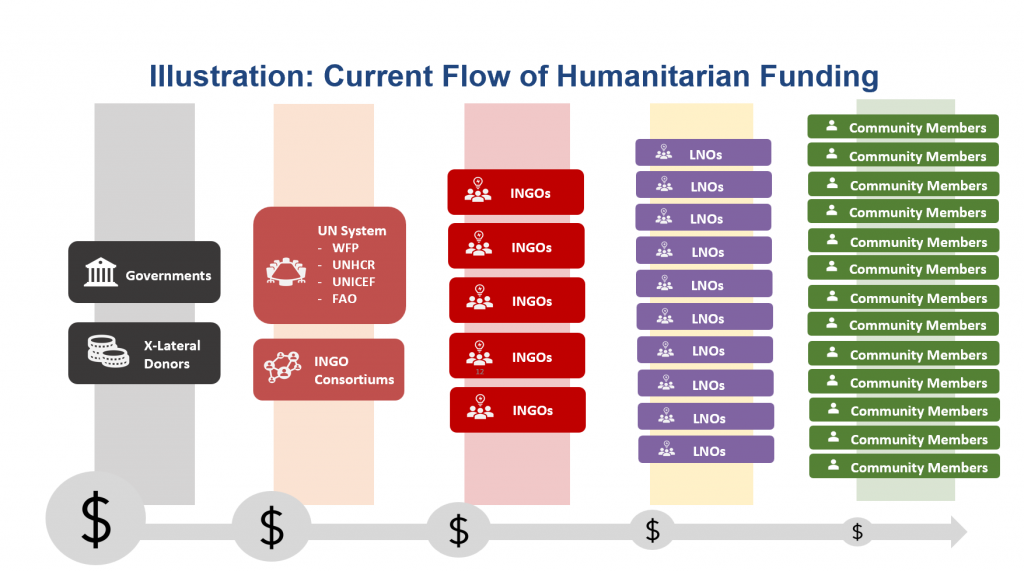

Here, there was a striking focus on efficiency/value for money, which is of course what floats economists’ boats. Can localization de-layer the traditional aid supply chain, through which multiple intermediaries skim their percentage off the top before passing on the shrinking pot to the next player down the line?

To de-layer, the donor should start with a flat structure (e.g. donor funds local NGOs directly), and then ask ‘what is the value of adding an extra layer?’ Working in this way could free up a lot of $ at a time of huge pressure on aid budgets.

As would making more use of local actors, and less of internationals. Headline finding: ‘local intermediaries could deliver programming that is 32% more cost efficient than international intermediaries.’

I’ll try and get my fellow panelists to blog their research on this.

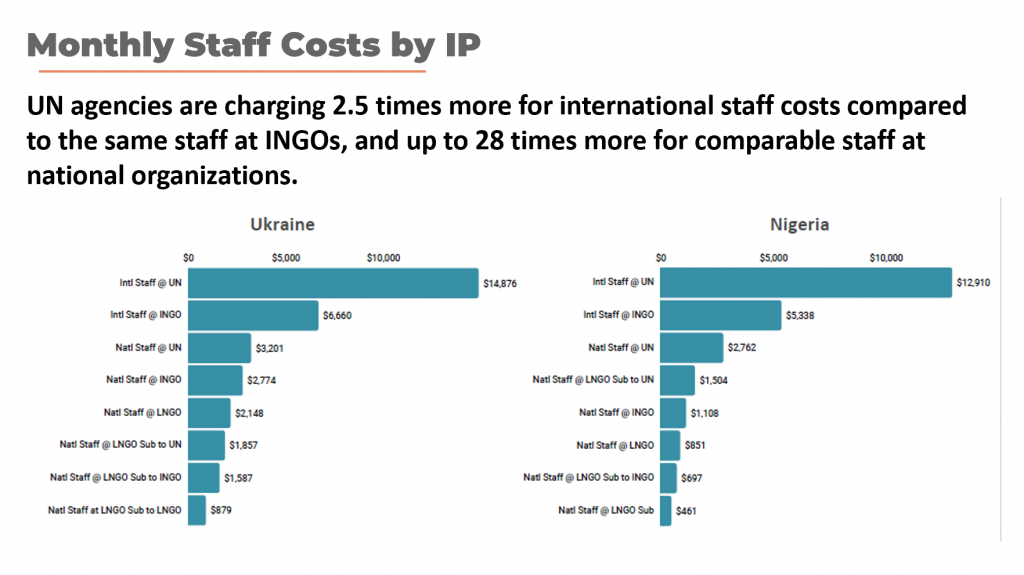

The UN comes out of this research particularly badly. They keep all the 7% overheads from donors, whereas INGOs typically pass on a portion of this to their partners, a form of core funding that enables local organizations to build their structures and capacity. Plus UN costs are much higher (see graphic).

Other parts of the conversation were more familiar to me:

- Discomfort with the word ‘localization’ (which itself sounds increasingly colonial – would a genuine local actor ever chose to call it that?). ‘Locally-led development’ is becoming more popular – the UK FCDO has an internal ‘Locally Led Working Group’, which sounds promising.

- Localizing is about a lot more than money. For example, knowledge. In Ghana, commissioning the standard political economy analysis from Ghanaian researchers rather than the usual fly-in-fly-out consultants got better results as well as strengthening local research capacity. Government officials were more likely to open up to homegrown consultants, especially when the interviews were conducted in a local language rather than English.

- Perceptions of risk are not the same as actual risk. In particular, research suggests local partners are no more likely to misuse of funds than international players. And that matters because of the cost issue: ‘Donors pay a high price for the perceived risk they are trying to avoid’.

- Churn: international staff rotate in and out after a few years, so never really understand the context they are operating in. ‘How do you manage risk if you are new to a country, which we always are?’ Suggestions included ‘pre-positioning your relationships’ – i.e. investing in a lot of networking as soon as you arrive in post, so that when a hurricane/earthquake/hunger crisis strikes, you won’t just turn to the comfort of the international aid business. Also, of course, listening to local staff, who know the country and do not rotate in and out anywhere near as fast – but that requires a big rethink of hiring and hierarchy within donor offices.

- No-one actually used the word ‘racism’, but the implication was clearly there (at least for me) – the business-as-usual preference for international organizations over national is often not based on evidence, but on prejudice.

I came away impressed at the seriousness with which this particular donor is addressing the issue, and wondering if we need a ‘friends of localization’ network/community of practice, bringing together advocates within donors, the multilateral system, INGOs and (of course) local organizations to plot and strategize about how to combine evidence, examples and advocacy to budge an issue that has been very stuck for far too long, but which feels ripe for progress.

But when I sent this draft to my fellow panelists, they threw up their hands in horror at the idea of another talking shop: partners ‘want to see action and solutions not repetitive consultation that tends not to advance beyond focusing on the barriers. I think the reason for lack of impact is that endless consultation manifests as a form of procrastination to avoid focusing resources on doing something about it.’

Views?

There are already communities of ‘friends of localization’ (or locally-led development). The RINGO project is a good place to start, with a 2000 strong community of allies. We have looked extensively at the barriers, but also sought to support innovation (real action, not just talk) in changing the processes and relationships between funders, INGOs and local actors. Some of the work is documented in my book, the INGO Problem. https://practicalactionpublishing.com/book/2938/the-ingo-problem#:~:text=‘,-Darren%20Walker%2C%20OBE&text=’This%20book%20is%20a%20powerful,but%20crucial%20questions%20of%20INGOs.

There is a strong economic argument in favour of locally-led development, but the barriers to shifting are all around power and racism and more, which is why many conversations focus on these issues.

We haven’t engaged as much with the multilateral system thus far, but our door is open!

There has also been a considerable amount of research done within the Shift the Power community about this, including the economics, with a report on ‘Too Southern to be Funded’ that looks at funding flows to local CSOs from bilaterals. https://globalfundcommunityfoundations.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/TooSouthernToBeFunded.pdf

Where are the consultancy firms in the diagram? Or do they not feature in the humanitarian system?

Good point. This is an example thematic. There is a significant role for the private sector to play in facilitating locally led and I have seen some great examples of them leading the way through partnering.

There is indeed already valuable research with interesting recommendations. I suggest to also take a close look at ‘Passing the Buck, the Economics of Localizing International Assistance’ by The Sharetrust and Warande Advisory Committee (November 2022) https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b2110247c93271263b5073a/t/6377d05b92d652286d6720e5/1668796508981/Passing+the+Buck_Report.pdf

The NEAR Network is another example of an existing “localization community of practice” that you are suggesting. . . https://www.near.ngo/ “NEAR is a movement of local and national civil society organisations from the Global South with a bold ambition – to reshape the top-down humanitarian and development aid system to one that is locally driven and owned.”

Within this approach, the unit of analysis is local peoples, and diversity need be celebrated as an inherent good—the objective in shifting the analysis away from the macro level, from states, and implicit belief in the well intentioned governments and instead to local realities on the ground and how actors at the local level have responded to global pressures and processes.

Crucial is focus on governance for development not on grand schemes and universal templates, but on experiments with hybrid forms of governance at local level implementation.

My extensive development experience directs me to this singular consideration—local people can make a difference. Clear salient is freedom in open choice constitutes a necessary pre-condition for action of peoples to promote their interests.

Focus on institutions is crucial however should not be based on universal or Western templates, but hybrid forms, adapted to local conditions and cultures. Obstacles intense exist for development in unclear overlapping ambiguous institutional mandates, incoherent policies and wrong or even perverse incentives—problems which can be addressed through local flexible programs involving peoples at the grass roots level encouraging an open democratic form of development trenching supported sustained by these local peoples.

Political freedom is not—you do whatever you wish—Inherent in freedom is that your freedom is limited by the need to maintain and enhance other people’s freedom.

Inherent in freedom is social civic civil responsibility.

The normative choice for freedom is inherently social as freedom implies we make political and policy choices and formulate laws that may limit our own freedom in order to protect or enhance the freedom of other individuals in our society.

Freedom implies that our political institutions facilitate collective action and create the right incentives to further social goals. Attempts to violate human freedom in the name of some higher goal, whether socialism, nationalism or developmentalism, have usually migrated into policies of discrimination, ethnic cleansing and violation of individual rights.

Crucial is the importance of freedom, broadly conceived inherent in any kind of democratic development program.

Localization is now one of the big focuses in our modern aid and development dispensation. However, a lot of people argue that the relevance of development aids can only be much felt with the presence of INGOs. While this might be true, the opposite might not always be correct. Local/National organizations know that they have a responsibility of upholding and maintaining donors’ trust while implementing any project or intervention in order to secure the next one. Besides, the future generations depend on those sound, critical and responsible decisions for survival and they (local organizations) just can’t afford to let them (the future generations) down.

I am of the strongest opinion that localization is a good step to reduce the middlemen activities between donors and the end-users (beneficiaries/participants). When local organizations begin to receive direct fundings from donors, we would have saved roughly 30% of funds already, as compared to it passing through several other higher up actors with numerous bottlenecks.

Another benefit of localization is that it is somewhat sustainable or cheaper to sustain as opposed to the other way round. Local staff are cheaper to hire and deploy in-field to enhance sustainability. Besides, they know the culture/customs of the people, can relate with them better, and collect and report existing feedbacks, both said and implied ones because they feel a connection with the people.

And of course, value for money, another bigger picture of the entire game comes in. A budget to maintain 10 foreign staff on a particular project can hire up to 20-30 local staff, depending on the HR Policies of each organization. However, with good training, the same job can be done by the local staff using less money to hire.

We must not just work hard, but work smart by promoting and investing in localization schemes and activities.

Second the suggestion of linking in to RINGO and other groups associated with the broader #ShiftThePower movement, rather than setting up another (ironically probably not locally led) group to discuss those! 🙂

As for me, since localisation has become a major concern across the development and humanitarian sectors. It is driving donor efforts to increase direct access for local actors to donor resources, as well as promoting local leadership and knowledge in donor-funded programming, it is important to formulate a framework for local actors to use as a guide in performing their work. It’s also an opportunity for local actors and the communities they work with.

It ‘fascinates’ me how these discussions concerning LLD, CDD, CBD and so on have been going in circles since the nineties or seventies even.

I second Ajoy’s question above (and respectfully disagree with Beverley slightly….).

Where are the (for profit) consultancies in this image / aid food chain?

My experience is that within the development (rather than humanitarian response) part of the sector, between Govt and INGO Consortiums there is often another ‘trophic level’ in the food chain.

For example often an agency like FCDO will outsource a huge swath of the funding line management to a consultancy firm like PriceWaterhouseCoopers or MannionDaniels. These guys then distribute (and ‘manage’) the funds allocated to INGO consortiums – and so on down the chain.

I’ve often struggled to see the additional value add these entities offer.

Localisation is one aspect of the change that is needed but if it is only about a more cost efficient, but still top down (from the perspective of a citizen / service user), approach to delivering aid then it rather misses the point.

Research in Malawi showed that when local people – in the form of separate focus groups of men, women and village elders/leaders – were asked three basic questions about a particular topic (what works, what doesn’t work and what should be done to improve the service) 90% of what locals recommended was the same as the recommendations of experts external to that locality or country. The radical difference was that when a shared action plan was developed by bringing those local service users, service providers and district officials together to discuss their different local views and together develop a shared action plan, the service users participants were frequently transformed from passive recipients of external (well intentioned and well designed) interventions into activist citizens who now saw the opportunity – and had developed the skills – to shape and contribute to the development of their own community and society. See examples on this facebook page https://www.facebook.com/ScoreCardGroup/

If external agencies and funders really want to localise their aid, then investing in this process at the start of their interventions can transform the impact of their work far more than just channelling the money for the implementation of existing projects through more local organisations that still operate as top down outsiders from the perspective of the local citizen who they intend to help.

The organisation that developed this approach in Malawi, is now seeking to operate as a social enterprise gradually emerging from within CARE Malawi and has delivered training and support across 20 countries round the world dealing with issues in 10 different sectors. That experience also illustrates some of the challenges of localisation as they seek to reconcile the financial backing and networks of contacts of such a large multinational INGO with the need for flexibility and innovation required to operate as a successful start up social business.

For more information contact Thumbiko Msiska, Technical Director, Cell & WhatsApp +265 999 951 834 or email at thumbiko.msika@care.org

DevEx recently published an article on the implications of a Trump presidency on global development, and specifically talked about how localization might be viewed under this new regime. They specifically mentioned Project 2025 and talked with the lead author of the USAID section of the Project 2025 manifesto (Max Primorac), and he stated clearly that value for money was one of the key lenses that a Trump presidency would focus on. “You look at sub-Saharan Africa, the faith-based organizations, the churches are running most of the hospitals and the education institutes, so working through them, I think there’s a lot of savings. They’re cheaper.”

https://www.devex.com/news/donald-trump-won-what-does-that-mean-for-development-108712?mkt_tok=Njg1LUtCTC03NjUAAAGWpXg__vY6ZxbD48RMTr_18cibvtNi9mrEaJiq82q67KnbX-0hmX4yPyA5vMPjvtURhJ06rNuHddftQ6PQZawuAskDZxh4eeA4btaYkuxx3e4q&utm_content=image&utm_medium=email&utm_source=nl_newswire&utm_term=article