The British NGO network BOND recently published a report on ‘catalysing locally-led development in the UK aid system’, which summarizes a six month project involving dozens of people from different aid organizations. I have to confess that I started reading with low expectations – there are a lot of pious exhortations on localization, which all too often ignore crucial issues of power and incentives. Not this one though, it’s really good, drawing on systems thinking and power analysis to try and understand why localization is not happening, and on positive deviance to identify and learn from some positive outliers. Ending in some crunchy practical suggestions. Some extracts:

‘This idea is not new. The 2016 World Humanitarian Summit resulted in the Grand Bargain – 51 commitments to encourage international humanitarian actors and donors to work more effectively and transparently and place more power and direct funding in the hands of national and local responders in the countries where development work happens. In the same year, the Global Summit on Community Philanthropy explored how to move away from hierarchical systems of international development and philanthropy towards more equitable people-based development, and was where the hashtag #ShiftthePower was first used. Covid-19, the Black Lives Matter movement, and changes to aid budgets have disrupted business as usual. This pivotal moment is our opportunity to present and imagine new ways forward – harnessing the power of collective action in the UK INGO sector – and to listen and respond to ideas in the places where INGOs work.

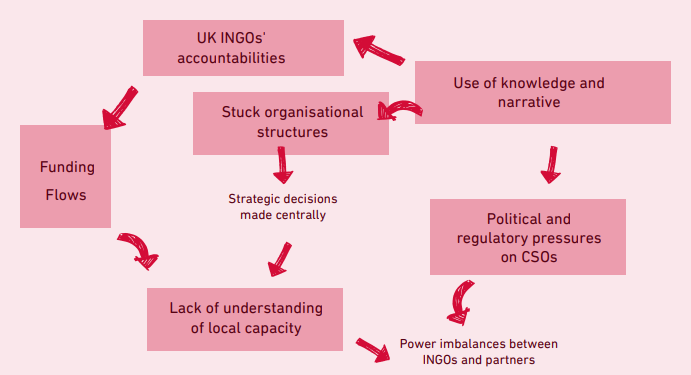

There’s a nice visual summary of the key factors driving/blocking progress

The 31 page report then boils everything down into ‘six heavily connected areas that describe the relationship between international and local CSOs.’

UK accountabilities

Increasingly, UK INGOs must demonstrate in-depth accountability to donors for a number of reasons, including declining support for UK aid amongst the general public and NGO scandals, such as those relating to safeguarding and CEO salaries. As a result, UK INGOs are perceived to be ‘better equipped’ than local CSOs to deliver programmes on scale and report back to donors. We identified the pattern in which INGOs and their partners can be hyper accountable to donors, and the limited structural incentives for direct accountability to local communities.

Governance and organisational structures

UK INGOs are predominantly staffed by white people, and their headquarters are overwhelmingly based in the UK. Headquarter staff make strategic decisions, secure funding and are the main contact for donors. Headquarters often absorb a percentage of funding and staff there earn more than staff elsewhere. Crucially, decision-making is the responsibility of people who too often have limited knowledge of local contexts. This model results in accountability flowing upwards rather than downwards.

Funding flows Donors are risk adverse.

Their preferred method for funding civil society is a system that uses policies and regulations that are based on UK laws. Their expectations and approach to risk, compliance and value for money are developed in the UK. Many funding mechanisms require the UK office to be the lead organisation. This reinforces a top-down relationship, where UK INGOs are in a position of power because they have the relationship with the donor and are responsible for completing due diligence on local organisations. This results in UK INGOs developing expertise in working with donors, including an ability to speak a donor’s ‘language’. All this prevents local CSOs from developing their own capacity to fund-raise, meet donor requirements and carry out due diligence. This creates a system that favours UK INGOs, enabling them to invest in fundraising and quality programme design. In turn, local CSOs are perceived as lacking in capacity and accountability to deliver projects.

Understanding local capacity

If local CSOs and national staff are excluded from strategic and programmatic decision-making, inefficient development interventions are likely. Voices of those most affected by the issues being addressed tend not to be heard and they lack decision-making power and resourcing. Communities and project participants can be perceived as passive ‘beneficiaries’ who need to have their skills built, rather than whole, active, and resourceful actors with the solutions to their own problems. INGO communications often perpetuate this stereotype and embed this damaging image into fundraising proposals and programme design.

Use of knowledge and narrative

Certain types of knowledge and expertise are more valued than others. Analysis, findings and knowledge pieces authored and developed in Western European countries like the UK or in the United States are often more valued than other insight. Expertise is often equated with academic credentials, and research, monitoring, evaluation and learning processes are often designed by those deemed to have the ‘right’ expert credentials. Entering the UK international development sector is competitive, and a requirement is for academic qualifications from elite universities, which means that lived experience tends not to count. Imagery and narratives often perpetuate negative stereotypes amongst donors and INGOs, which feed into the ideas of ‘developed versus developing’, beneficiaries rather than co-creators. The dominance of the English language also means that knowledge and learning products are developed by, and cater for, native English speakers.

Political and regulatory pressures on CSOs

Increased political restrictions and regulations for CSOs can often mean that accessing funds from overseas is challenging. Some governments that are hostile to CSOs impose restrictions on them, suppressing networks and political activity.

And another nice visual summary, this time of possible ways for INGOs and others to take action

My only caveat is the lingering attachment to the ‘illusory we’. When it comes to INGOs, the report tends to argue that ‘we’ need to do X,Y,Z, but INGOs are themselves a diverse system, full of incentives and feedback loops that can encourage or frustrate change. What drives a press officer is different from a CEO, a fund raiser or a programme manager. They will have see localization differently depending on where they sit. And that shapes how organizations behave.

But all in all, this report seems like a really good starting point for any aid organization embarking on a discussion on localization.