I had a lot of fun with Save the Children last week, whose advocacy team asked me to talk to them about ‘Research for Impact’. The fun started even before the talk – I idly tweeted the night before asking people what their ‘commonest moans’ were about NGO research. Obviously hit a nerve – 56 responses and counting.

Tweeps. What are your commonest moans about INGO research? Talking to Save the Kids on research for impact tomorrow, and put together this list pic.twitter.com/pAq2m4i7Ri

— Duncan Green (@fp2p) November 29, 2021

I updated that slide from the responses in my ppt (slide 15):

I was glad I kept my blah blah down to 30 minutes, because the questions were much more interesting, sparking new connections (at least for me) and sharpening ideas – here’s a sample, with my responses

Save: we’re shifting to more community-oriented/localized way of working, including in how, why and where we generate evidence. Are there any principles that you think are particularly important for a hyper-localized way of working?

DG: hyperlocal lends itself to

- Implementation. Every news piece starts with a person who was affected by X – localized research is ideal for providing those examples

- I’m a big fan of temoignage – ‘bearing witness’. French NGOs have built up a reputation for being on the ground, and able to capture people’s voices

- Linked to that is some work I’ve been involved with IDS is systematizing that through diaries, a really interesting methodology where you work with a local university and get students to keep going back to the same families and talk to them about the same issue – this builds up trust and helps construct a long-term picture, through the eyes of the people at the bottom. It has huge potential.

Save: Do you separate out advocacy from research, or do you combine them?

DG: It probably doesn’t matter that much. The underlying trend is that we have less and less control over how our ‘products’ are consumed. Imagine, back in the day, a thinktank or NGO would be stuffing envelopes with their latest report and sending them to decision makers. You knew who would receive what, so you could segment the market, send some things to some people, other things to others. You can’t do that now. Everyone can see everything. If you say something that is clearly not backed by the evidence ‘because it’s a piece of fund-raising and who cares?’ someone else will get hold of it and you’ll be punished.

In Oxfam, some people say we are publishing too much. I’m not convinced (except for the poor sods who have to do all the editing and proof reading). In terms of the consumers, they don’t know or care whether we produce too much – they don’t have to read it all. Does anyone say ‘we have too many restaurants’? No – restaurants succeed or fail through natural selection, and the same happens with our policy papers. Some get picked up, others disappear, and that’s fine. The best thing is to find a low cost, low risk way of churning out useful stuff and then see what gets traction.

Save: You mentioned that it’s better to respond to debates and events, rather than try and impose your own agenda, but we have priorities that are part of long-term consultations and multi-year strategies. For example we have 3 big priorities – Climate Change, Covid and Conflict. How do we strike that balance?

DG: I agree that if you just chase the latest fashion, it damages your credibility. But if you have 3 topics as broad as those, you can usually find something to say related to the issue of the day. Then we can come to politicians with things that are adjacent to what they want, and in line with what we want. Beyond that, it’s about having criteria for when you say ‘this is a really big opportunity’, and everyone has to be ready to drop their existing research plans and seize it.

Save: On relationships, how do we go about building those? What proportion of our relationships should be with people in our sector, or with civil servants?

DG: Try and build reputations during peacetime – go to the webinars, interview people. Then they are more likely to listen to you during a crisis, when decision-makers are more open to new ideas. It’s a Forth Road Bridge job, requiring constant renewal, because people are constantly moving on. There’s nothing more frustrating than investing hugely in a politician, and then they’re transferred to some other department. Officials tend to stick around a bit longer. If you can build your reputation as an institution, that saves a lot of time.

Then there’s what you say to them. I tell my academic colleagues that saying ‘it’s more complicated than that’ or ‘everything is context specific’ is a surefire way to lose a decision-maker’s interest. I guess the equivalent for an NGO is saying ‘you haven’t consulted enough’ or ‘we you need to spend more money’. What else have you got other than more meetings and more money?

On getting out of your own organization, why not ask IT to measure what percentage of each person’s emails come from Save, from other NGOs and beyond, and then publish it internally? The results might be very interesting!

Save: Why is it so hard for INGOs to work with thinktanks and universities? It seems so obvious, and yet we struggle.

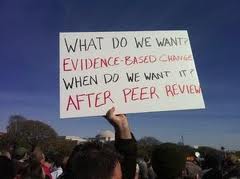

DG: Academics timelines are much longer – their incentive systems are to publish in peer-reviewed journals and books. The Research Excellence Framework, which partly funds research according to proof of impact, has helped a bit, but even then, often academics seek to instrumentalize NGOs to use their research. They don’t necessarily want to create it together. I think you have to really invest in one or two relationships over time, give PhDs access to your data, exchanging staff (part of my role as Professor in Practice at the LSE is to build those bridges). But it’s slow and frustrating. People are scared in both academic and NGOs, but they’re scared of different things – a lot of that fear stops people collaborating. Which is where thinktanks come in – they can move between the two, so maybe those relationships are more feasible.

Thoughts?