Oxfam’s Amy Croome reports back on a very different kind of localization discussion

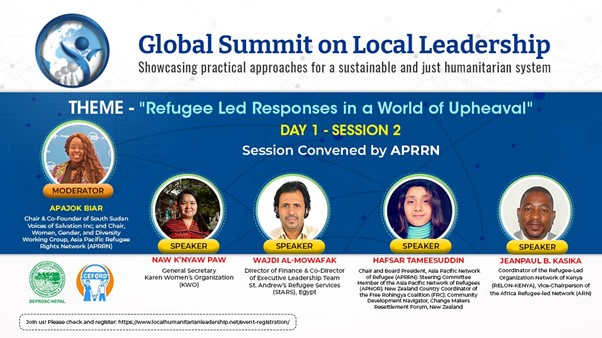

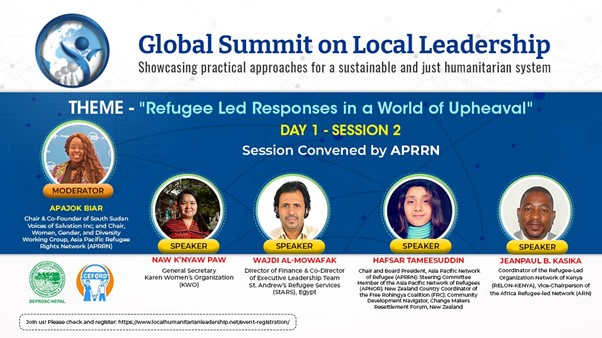

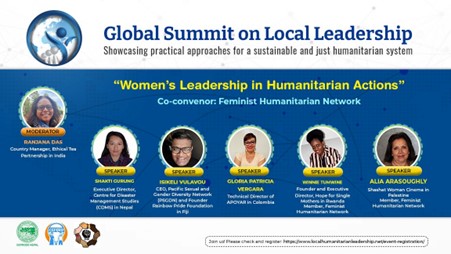

What happens when you bring together local activists and organisations to discuss how to reform the humanitarian system? I recently found out, attending a conference, where more than 85% of the speakers and moderators were from national and local organisations (compared to not even 10% at the European Humanitarian Forum). In five panel discussions and four learning labs over the course of two days, over 500 people from around the world discussed new financial models, refugee leadership, women’s leadership and transforming the humanitarian system. Here are my top take-aways:

Being inclusive is a lot harder than it looks, but in the long term, can radically alter the balance of power within humanitarianism

Listening to the panel discussions of women and refugee leaders showed how the systemic and structural issues of/in a humanitarian response are interwoven and the importance of connecting to development and human rights work.

Isikele Vulavou, CEO of the Pacific Gender and Diversity Network, when asked about what needs to change to have more LGBTIQ+ leaders in the humanitarian system, replied: “general acceptance”. Going on to explain how humanitarians operate with the acceptance, consent and coordination with community leaders, village leaders and elders and that when these leaders and the communities they represent do not have general acceptance of LGBTQI+ people, there is no space for these people within the humanitarian system. Implications? If we’re serious about inclusivity, we may have to invest seriously in shifting norms, which is long term, complex and difficult, but unavoidable.

Gloria Patricia Vergara, Technical Director to APOYAR in Colombia said we [humanitarians] need to create the conditions and hone our skills to be able to hear, listen and respond to women in crisis moments. It is not enough to say, “I asked her and she didn’t say”, Gloria explains this means you still need to learn about feminist humanitarian ideas.

Alia Arasoughly, CEO of the Shashat Women’s Cinema, added that women have been conditioned not to voice or even think their own needs, so how without the right approach would we even be able to respond to them?

Amongst core humanitarian issues, refugee leaders highlighted resettlement, underlying causes of a crisis that displaces people and the capacities possessed by many who have been displaced. This adds richness to the flawed distinction between ‘beneficiaries’ and ‘humanitarian leaders’ or between ongoing human rights issues, development initiatives and humanitarian responses.

Lots of interesting new ideas:

Many interesting new ideas and suggestions for how to improve the humanitarian system were brought to the table by local leaders – too many to list here, so let me pick one to highlight: Instead of having different agencies, INGOs and then local actors subcontracted to work on, say, education in IDP camps in a given humanitarian context, why not just choose one local organisation to be the lead for the sector across a given area, perhaps in partnership with the existing system of lead international actors? Bai Padoman Guro Paporo, of Marawi CSO Convergence Group, argued this would make coordination simpler, avoid duplication and would increase accountability. So, it would be easy to for example ask: Are WASH provisions meeting people’s needs? If not, speak to Titi Foundation as well as Oxfam (which often leads on WASH). Would be curious to hear if readers know if this does indeed increase accountability and avoid duplication.

Having a ‘majority world’ event is fundamentally different:

“This summit is an answer to our prayers” said Bai Padoman Guro Paporo, of Marawi CSO Convergence Group. Whilst in the Opening Ceremony, Dr Puji Pujiano, said he wished he had had such an event and group to guide him while acting in a leadership role within the Grand Bargain, as he felt he was “standing on a cloud”.

Aydrus Daar, Director of WASDA in Kenya and Somalia, says “due to financial constraints, local actors do not have the opportunity to learn from others. International partners do not allow their partners into their systems to learn for reasons that are not clear to me. Even local actors in the same locality don’t cross-learn due to high competition for scarce resources”.

So much respect for long term localisation advocates: If I am starting to tire to hear the common rallying calls, how must local actors feel?

For anyone who has been following or involved in localisation efforts in the humanitarian space over the last few years, you will be familiar with some of the common – and valid – rallying calls for what needs to change: redressing the power imbalances, more trust in those who are responding first and who don’t leave once the initial crisis is over, more funding for local actors, reducing due diligence requirements. From refugee leaders: nothing about us, without us. From women leaders: women are those who are on the frontlines but they and their needs are underrepresented in the system.

All of these of course were brought to the table at the summit and initially I was disappointed, because I wasn’t hearing these issues for the first time. But quickly it turned into awe: if I am starting to tire of these issue, what must it be like to be working with them for years, repeating these to INGOs, UN Agencies and donors over and over again, yet experiencing precious little change?

Angelina Nyajima Simon Jial, Executive Director of Hope Restoration in South Sudan, worries that the localisation discussion is being used by everyone to further their own agenda, and for local actors it is primarily about increasing their funds. But who can blame them given only 1.2% of the total global humanitarian funding is reaching local actors directly, while there is no global or national reporting against the Grand Bargain pledge of 25% going ‘as directly as possible’ to them?

Some of the most powerful interventions came from refugee leaders. Jean-Paul Kasika, Vice Chair of the Africa Refugee Network, summarised some of the core issues when he said “we are being locked out – how can we work together with our big brothers”. Refugee leaders are trusted as incentive workers, as subcontractors, but “why not as consortium partners?”. Naw K’Nyaw Paw of the Karen Women’s Organisation, asked about accountability issues of refugee-led organisations, replied that they are responsive to their communities, to the people around them, to the IDPs and refugees and are arguably therefore more accountable than say UNHCR, asking: “who are they really accountable to?”.

The virtual summit was organised by CEFORD Uganda and DEPROSC Nepal, opened by Dr Puji Pujiano and supported by Oxfam. Later in September the recordings and a synthesis report of the event will be available here and recordings are available here.