Guest post from Jess Crombie. Jess is a researcher and scholar at UAL, and a consultant for some of the leading organisations in the humanitarian sector.

The term Poverty Porn (coined in 1985); the widely criticised (though still widely played) song ‘Do they Know It’s Christmas’; the Lammy/Dooley scandal around Comic Relief; the brutal murder of George Floyd, sparking worldwide awareness of the Black Lives Matter movement. The INGO sector has had decades of nudges (and harder blows) to help it realise that the stories it tells don’t just raise money for projects, but also educate, and not always in a positive way.

The authors of a new study, ‘Charity Representations of Distant Others’, argue that these nudges have been heeded and that change is happening; “if the number of INGO ethical communications guidelines publicly available are anything to go by, much progress has been made”. This positive overall argument is a pleasant one, especially for the core readership – fundraising and communications professionals – but I’m not sure that the data revealed in this study supports such cheeriness.

What I suspect – and what this report also seems to demonstrate – is that while there may be growing internal awareness of the need to change, externally (for audiences of charity communications at least), not much has shifted. Authors Deborah Adesina and David Girling have created a data set which will surely be catnip to students of international development. They have made available a database of six months of charity advertising, placed in all the UK weekend nationals in 2021, and featuring 363 adverts. The accompanying research paper is described as a “snapshot of evolution and trends in charity representation” designed to draw some topline conclusions and continue a conversation about what charities choose to depict to raise funds, and why.

The research methodologies and some of the analysis lean heavily on previous studies, namely Nandita Dogra’s excellent 2012 ‘Representations of Global Poverty’. While Dogra’s study is certainly more in-depth, I doubt many of the staff working in the organisations discussed have read her book. In comparison, this short and topline report is clearly focused on charity fundraising and communication professionals, and arguably therefore much more likely to have impact.

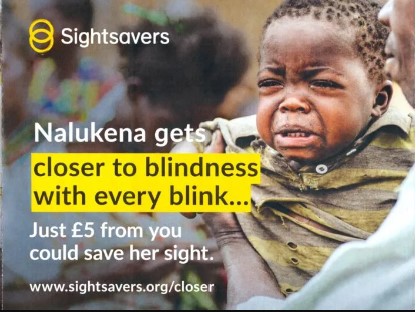

The positive overall headline is supported by two key findings. Firstly, a drop in the use of children as the predominant faces of charity advertising from 42% to 21%. This seems to demonstrate a growing awareness of the need for greater diversity, but also a move away from the saviourist trope of suffering Black/Brown child in need of western donor support. Secondly, we can see a significant drop in the number of images categorised as ‘pitiful’ (“people were visibly suffering from malnutrition, illness or hardship: crying, bleeding, dirty or sick)”. In the entire study only two met this criteria, produced by Sightsavers and Operation Smile.

This move from ‘pitiful’ to positive is one that I have seen pop up regularly as a favourite action by fundraisers wishing to make changes to their depictions of poverty. While tangible actions towards change are always to be celebrated, this one seems to dodge the point of making that change. Positive stereotyping (they’re so happy even though they are poor) is just as ‘othering’ as negative stereotyping (they have nothing and need your help). I’ve always suspected that this is the space where charity fundraisers feel most comfortable as it doesn’t require a big move from the fundraising rules that exist and are followed religiously (percentage of text vs image, eyes to camera, precisely what point in the text to place the ‘ask’, always thank the donor etc). Instead, it’s a lift and a shift which does not require the admittedly more complex but ultimately more transformational work that is adding context and nuance to stories.

The study also reveals that most of the traditionally repeated stereotypes are still front and centre. “The majority of photographs used by INGOs have a similar theme. They are usually of children, or women and children, and depict rural areas and poverty. As a result, whole areas and regions of the world can become reduced to poor women and children living in ‘unnamed rural places’”. The authors were also able to demonstrate that Africa is still the predominant subject of charity appeals, with more than half of the adverts depicting the continent, even when this does not reflect the ratio of programmatic delivery at the organisations producing these ads. The researchers conclude that “this continuous majority casting of African nations in the theatre of global development as recipients of humanitarian assistance, serves only to aid and abet the colonial notion of Africa as one huge ‘begging bowl’”. And that the impact of this is even more concerning, “there is evidence to suggest that the UK public views ‘developing countries’ as synonymous with ‘Africa’ and associate Africa with poverty and misery”. This is not new news sadly, but it is important to have this data set as a stark reminder of how much has not changed.

In debates around how to add context to storytelling, the issue of naming individuals depicted often comes up. These adverts showed that only 55% of individuals photographed were named (although this did not account for those in groups, and those whose names were changed to protect their identities). The authors advocate for naming everyone in images, arguing that without this there is an implication “that the subject is rendered as good enough to validate and legitimise western development intervention, but not good enough to enjoy the privilege of representing her/himself.” Naming people has been regularly cited as one of the most basic steps that any organisation can take to move the dial from ‘subject’ to ‘human’, but I’m not sure that naming someone moves them from ‘subject’ to a place where they are enjoying the privilege of self-representation.

What was also revealed was how much depictions of global poverty were dominated by the ‘big four’. MSF (double the amount of adverts of any other organisation), followed by UNHCR, UNICEF and the British Red Cross. The power of the marketing spends behind these big organisations reveal how much impact they have in creating and maintaining narratives about aid and poverty.

Adesina and Girling have pulled together an easily digestible slice of charity advertising analysis. The authors themselves say that it is neither “comprehensive nor conclusive”, but I think it will give many in the sector space to reflect. Personally, I would have liked to have seen them show sharper teeth when it came to their conclusions and the pace of change. If the length of time that this debate has been running shows anything, it is that for those creating this content, reflection alone is not enough to effect change.

Really good to have something empirical on this, thanks for posting. Jess/Duncan, are there any comms examples that you (or the authors) consider to be good practice?

Hi Anita, thanks for the comment. There is loads of change happening, but a lot of it is hidden and internal. Some of the public pieces are ones I’ve worked on and available on my website Jesscrombie.com, I specifically recommend the Amref project I worked on with David Girling. You should also look at Chance for Childhood’s #overexposed campaign and MSF Norway’s anti racism video. Both are examples of organisations who told their donors they want to change and asked them to change with them, neither saw any negative results.

I’m just catching up – apologies and thank you, I’ll take a look! Interesting that the impact was the same (and I wonder if that would be consistent across the board w.r.t. issues, regions etc).

Because the subjects of poverty and development are rarely taught in schools nor covered deeply, sensitively or accurately in the media, the reality is that most people get most of their information from direct mail and adverts from charities and NGOs. We are our own worst enemies! What enormous potential we have through our own media to tell a different story and help the public truly understand the nature and causes of global poverty.

Hi Bill. Thanks for the comment. We’ve been collecting two years worth of Direct Mail from charities and NGOs. We will be sharing those on our website in due course….

Will be interested to hear what the direct mail comes up with and whether there are marked differences in tone and style public messaging vs talking to (somewhat) more engaged and captive audiences on mailing lists. I’d like to think there is but have seen an awful lot of generic “This is Ayesha. Her life is rubbish. Just imagine it. You, Brian Sample, can make a difference. Give now. Thank you. PS: Give now.”

I couldn’t agree more!

Thanks so much for that Jess – great piece! I think you’re absolutely right that some of the questions miss the more important bigger picture. In Health Poverty Action we see that as more about the overall narrative the communications perpetuate (either explicitly, or by failing to challenge the public’s most likely assumption).

The very terms ‘charity’ and ‘aid’ convey a benefactor/need relationship. That framing’s so deeply offensive (not to mention counter-productive) if the real thing that needs changing is the disparity of power and wealth. We argue that what ‘s needed is a shift from the narrative of aid and charity (and maybe even from eradicating poverty) to a narrative of solidarity and tackling inequality.

We think that narrative ultimately plays better with the public too. The communication of course then needs to be tailored for different audiences. But that can be done. It doesn’t have to use lefty concepts that speak primarily to people like us. It’s basically about levelling up on a global scale – including a focus on the size, causes and consequences of extreme inequality.

(You then don’t need to show people happily enjoying their experience of this injustice. It’s fine to show outrage and other emotions.)

Absolutely. There is a lot of research that various orgs are doing (which is not public sadly) which shows that the UK public are a little behind the orgs in this debate, but that they are changing their views to look for less stereotypes and more nuance in storytelling. The research also shows that there is significant reputational risk with not shifting their understanding due to growing media and commentator criticism in this area too.

I’d be very interested to see something around trends in the wider level of engagement of global populations with affected people in other countries from *any* perspective – I’m constantly shocked at the low level of worldwide interest in affected people in lower profile contexts like Sudan – which has suffered almost certainly a higher death toll than Gaza in the last year and just as egregious breaches of humanitarian law. This is despite inspiring narratives of Sudanese citizens fighting (largely unsupported by anyone) for their own rights over recent years, and is as true in Indonesia or India as it is in the US or UK.

Martin (above) is spot on with solidarity, but I think inequality is a much more challenging lens, as those with power often see such framings as ignoring their own closer-to-home challenges and thus low on their priorities, which contributes to the current catastrophic gap between what affected people say they need and what is provided by *any* actor, including their own governments, local actors, development actors, political actors, military actors and the international humanitarian ecosystem

Hi Gareth, the only data I know of that may help is from devcomms (https://developmentcompass.org/data-and-surveys), and their studies focus on US, France, germany and UK population atttiudes and behaviours towards humanitarian aid and development issues.

Thanks @James. That put me on to the aid attitudes tracker – but its a bit dated. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/government/departments/international-development/research/projects/2019/aids-attitude-tracker

Yes, this is a broader issue and one that is affecting all of the funding for humanitarian causes (not just from individual givers like those studied in this research).

Foreign aid always gives me a bad feeling, especially when it is so badly advertised and they demand recognition.Foreign aid is not a panacea.

What better tools to address diseases of poverty, have providing these agencies full of bureaucrats without creativity and compassion?

It’s about helping them learn how to continue to be sustainable and live.

They need to ensure that funding recognizes, respects and builds on local resources and assets, rather than over looks, undermines or displaces.

“By pouring money and goods into devastated regions, foreign aid workers sometimes compound the disruption and debauch the survivors” James Buchan

Poverty eradication is an obligation, not a charity. Prof. M. Yunus

Presumably, charities use these images because they motivate more action, raise more money, and thus save more lives, prevent more infections, etc.

What’s the maximum increase in suffering and death that you would be willing to make people in the Global South “pay”, in order to avoid these images of reality being shown to people in the West? 1%? 10%? More…?