Guest post by Emily Hayter, with one of the more improbable FP2P opening paras…..

“I work in the evidence-informed policy sector” is always an interesting opener at personal and professional gatherings.

I started out in the 2013 Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence initiative funded by the UK. Since then I’ve worked on a number of initiatives around the world, most recently as the lead on Evidence Use at OTT – a global consultancy and platform for change.

Over the years I’ve noticed a few common themes that come up within the first five-minutes of conversation that follows. See what you think.

Question: Evidence use is political, right?

Answer: Yes! Like any aspect of public policymaking, evidence use is closely intertwined with politics.

Politics is often mentioned as a “barrier” to evidence use. The assumption seems to be that if only politics would get out of the way, then people could get on with the serious business of evidence use.

But politics is a fundamental part of any democratic system, and even though it can be challenging to navigate, I don’t think any of us are looking for a dictatorship of scientists either. The thing that’s interesting about evidence use for me is how evidence can interact with and be integrated into democratic systems. And there are lots of different tools and approaches to help understand and address this.

It means that those who are working on it need to keep an eye on both the technical and the political. This goes for any aspect of public sector governance—from public financial management to procurement, decentralisation or electoral reform. It’s part of what makes the sector exciting to work in.

Q: Do policymakers even care about evidence?

[Usually asked with a strong tone of scepticism and sometimes a note of condescension.]A: It depends who you mean by policymakers. Often people use this term to mean the political layer of government. In many countries’ national development plans, there are high-level statements about building knowledge economies and engaging with the fourth industrial revolution.

The extent to which individual politicians are personally interested in and committed to these statements of course varies enormously, and with high turnover rates in elections that means a constantly shifting landscape.

However, one thing that’s often forgotten is that the politician is unlikely to be the person who invests time in reading an entire piece of research or combines it with other research to inform a decision.

The policies that politicians decide on are designed and implemented by the technical layer -the civil servants. These are the people who are weighing up different courses of action, providing briefing papers on possible implications and costs of different avenues, reviewing progress of policies that are already being implemented, identifying evidence gaps, commissioning new evidence and so on.

I haven’t met a civil servant yet who isn’t interested in what the evidence says about the issues they are working on.

I have, however, met people who have limited time, poor access to evidence, often chronically underfunded and understaffed internal research and evidence teams within their ministry or department, and who are justifiably daunted by the prospect of aggregating and communicating enormous and complex bodies of evidence, of different methodologies, into briefing papers in a short period of time to inform decision-making.

I’ve also met committed champions within government who are spearheading new and innovative ways to improve evidence use.

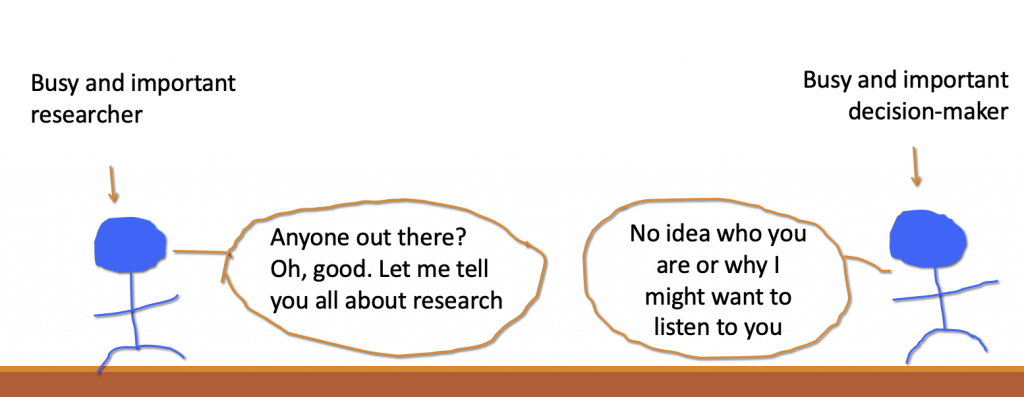

So for me, the key is understanding those evidence users, how it feels to walk in their shoes and what their practical needs and realities are. Some of the challenges of communication between researchers and policymakers are expressed succinctly by Ruth Stewart, founding Chair of the Africa Evidence Network who has kindly let me reproduce her cartoon from an old blog here:

Q: What kind of evidence are you talking about? I think [insert favourite method here] is the best one.

A: One of the first implications of taking a user-centred approach to evidence is recognising that multiple different kinds of evidence are combined in decision making, as pointed out by the ODI’s Research and Policy in Development team in 2012.

The most common and overlapping categories of evidence I hear people talk about are things like, citizen knowledge, research, statistics, practice-informed knowledge or stakeholder consultation.

Different types of evidence will be more suitable for different types of decisions. Bu it’s much more likely that evidence of different methodologies, sources and disciplines will be combined to feed into an understanding of a policy problem or potential solution than policymakers relying on one type of evidence alone.

My sense is that the methodological debates seem to be more relevant for evidence producers than for users.

Q: How can we measure when evidence is used?

A: This is the million dollar question, and of course it’s one which donors are particularly interested in.

There are more forms of evidence use than we might think! And there are various ways of measuring evidence use. It’s important to remember that drawing on one piece of evidence for one decision is a small part of this.

Much of the focus and preoccupation of the sector as far as I’ve seen is on how to build routine evidence use within organisations, also known as ‘process use’ or ‘embedded use’. This means building evidence use into the everyday machinery of government, so that on an ongoing basis and as part of planning and budgeting cycles, organisations are identifying their evidence needs, planning for them, liaising with researchers within and outside government and—crucially—applying the evidence to the right decisions and the right time. The new Global Commission on Evidence calls this the ‘domestic evidence support system’.

That is in some ways a messier, more long-term endeavour than having one piece of research influence one decision—but the rationale is that it’s hopefully also more sustainable in the long term.