By Prachi Srivastava, Associate Professor, University of Western Ontario

Nous sommes en guerre. ‘We are at war’—President Macron, 16 March 2020.

With global attention rightfully focused on immediate health impacts, the fact that COVID-19 has brought about an unprecedented immediate global education emergency of unimaginable magnitude, is now catching attention.

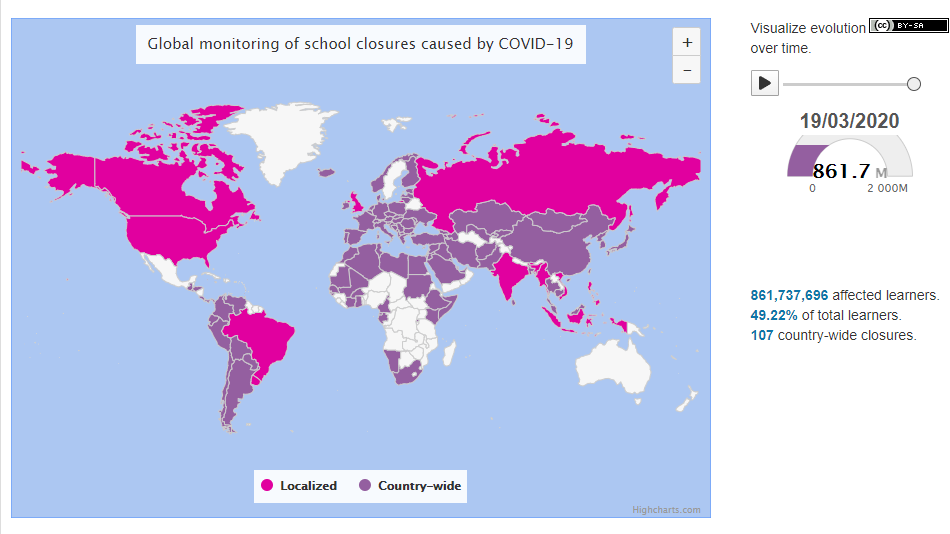

On 4 March 2020, UNESCO released its first update on the number of children out of school due to nationalised school closures in response to the pandemic. That number was 290 million in 22 countries. Just two weeks prior in February, China was the only country to issue closures. As of 18 March, 107 countries have implemented nationwide closures, which affect over 861.7 million children and youth.

According to my rough estimates using the World Population Prospects 2019 data, there are 1.91 billion children and youth aged between 5 and 19. That means, at minimum, the education of 45% of the global population of school-aged children and youth is immediately disrupted due to the impact of COVID-19.

This is a minimum estimate.

It excludes children and youth in an additional 12 countries with localised school closures (including, among others, Brazil, Canada, India, Russia, the US), a number of which have substantial populations. It also excludes the existing 250 million out-of-school children due to entrenched inequities. As they are already from the most vulnerable groups, likely, they will be even worse-off in the pandemic.

The scale and speed of the disruption threaten the right to education.

Compulsions on the State

States are the principal duty-bearers under international human rights law to uphold the right to education. The State must respect, protect, and fulfil that right. In times of emergency, these obligations are heightened. (I’m not saying there’s no room for partnerships or non-state actors — but the duty is on the State to act).

The State must ensure that the impact of the pandemic is minimised on accessing, transitioning, and completing education through the system. Yes, transitioning and completing.

We need to accept that temporary school closures of two to three weeks are probably unrealistic in most contexts.

What does this mean? Considerations for a Plan of Action

States and local governments must act quickly and with concrete medium- to longer-term action plans. Plans should be publicly disseminated in communities and to parents and the general public. Messaging should be clear and direct.

It means transitioning to alternative delivery, which may include a blend of grade- and school-specific special television programming, radio broadcasting, and virtual and online learning. There is room for innovation, however, delivery should be organised according to the curriculum in a structured way. The transition requires quick action to involve teachers in the process, and probably, training in new modes of delivery.

It also means thinking systems-wide and cross-sectorally. If there are prolonged school closures, equivalency measures may need to be introduced so that students can transition to higher grade levels or through the system (i.e. elementary to secondary, secondary to post-secondary, etc.). Revised school calendars may need to be instituted. Alternative assessments and temporary leaving qualifications may be required.

If there is no provision for a substantial period of time in some communities or for some groups, ‘catch-up education’ programs may be required, the kind that have been implemented in Uganda for girls or during my time in Kosovo by UNICEF and the International Rescue Committe for Roma and Ashkalia populations. ‘We’ in the North/West need to look to the Global South and to emergency and conflict-affected contexts for lessons in emergency response.

Image: CDC/Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAMS

Cross-sectorally, measures must be instituted to extend other social services to children and families who depend on schools as hubs for meals, special care, allied health services, and counselling. They often cater for the most vulnerable. Using closed school spaces to help manage the pandemic for overflow of patients or for quarantine may be another cross-sectoral response; or to provide childcare for essential services and frontline workers (e.g. Netherlands), such as nurses, doctors, teachers, pharmacists, grocery shop workers, and cleaners, if at all feasible.

None of these are ideal. All will have trade-offs. But, special circumstances require special measures.

Challenges and Risks

All of this is easier said than done. In many countries, education systems are decentralised. There may be variations in the structure of local systems within country and in the curriculum. There may be no national department or ministry of education, making it difficult to implement a coordinated response. Education may already be under-funded prior to the pandemic, keeping in mind that one in four countries do not meet the education finance targets of 6% GDP or 15-20% budgetary allocation.

There are also equity implications. What about those who cannot access specific technologies? What about special needs education? What about children who are in circumstances where immediate caregivers cannot or do not have the resources to support them? These are all urgent considerations.

However, the consequences of ad-hoc or too little action by the State are dire. Education interruptions disproportionately affect vulnerable groups regarding learning levels and drop-out and retention. There is an immediate economic impact on families. The longer-term economic impact of substantial learning losses on societies can be severe. Given the number of children and youth affected without a clear timeline for interruption, this is a very real risk.

What is the global response?

The International Federation of the Red Cross, UNICEF and WHO issued guidance to protect children and support safe school operations in view of COVID-19.

UNESCO established a COVID-19 Task Force for advice and technical assistance to governments. It held a virtual conference with education ministers to discuss priority needs.

As I write this, UNESCO announced the launch of the Global COVID-19 Education Coalition, that ‘brings together multilateral partners and the private sector, including Microsoft and the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA), to help countries deploy remote learning systems so as to minimize educational disruptions and maintain social contact with learners’.

The Global Partnership for Education states that it will support partner governments affected by school closures and economic impacts of the pandemic. The modalities for distribution are being worked out. We have yet to see how the other global funds for education, in particular Education Cannot Wait, will respond. Or, if or how any of the $14 billion package announced by the World Bank Group to ‘fast-track financing’ ‘to prevent, detect and respond to the rapid spread of COVID-19’ will be used to support education.

In many domestic contexts and globally, we’re not there yet. But we need to get there fast.

Dr. Prachi Srivastava is Associate Professor in the area of education and international development, University of Western Ontario. She started her career working in conflict-affected contexts in education in emergencies with international NGOs, the International Rescue Committee, and UNMIK. Prachi.srivastava@uwo.ca. Twitter: @PrachiSrivas