To mark this year’s 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence, Oxfam’s Dana Abed introduces its new report: The Assault of Austerity: How prevailing economic policy choices are a form of gender-based violence, (here’s the online summary with graphics).This post first appeared on Oxfam’s Views and Voices blog

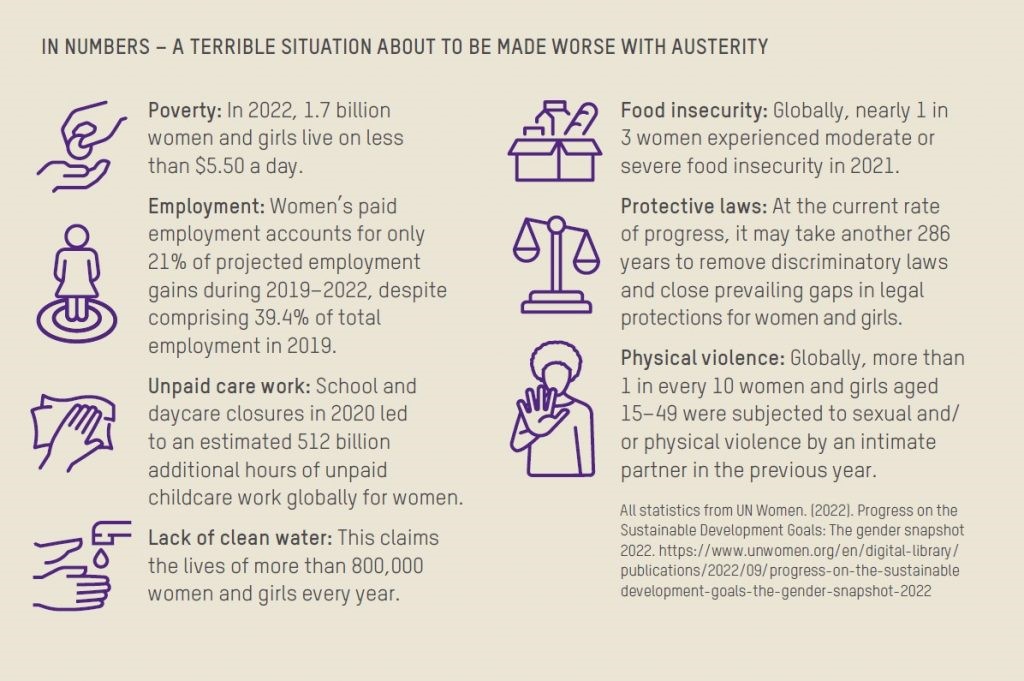

Feminist economists have warned for years that the global economic system is violent towards women and girls. Women in the workplace are too often poorly paid and exploited, denied basic rights such a pensions or maternity leave; hundreds of millions of women are in informal work that traps them in poverty. This stark gender injustice in the economy combines with patriarchal social norms and laws to keep women oppressed and their needs neglected.

But today, the situation for women in the global economy looks even more bleak. As countries around the world take a hard look at their balance sheets post-pandemic and as we go through the cost-of-living crisis, most governments are looking to cut services and introduce austerity measures. Their policies too often look set to protect the rich and the elites of society while imposing more economic pain on the marginalized, including women, girls, and non-binary people.

That’s why our new report for this year’s 16 Days of Activism against gender-based violence campaign highlights another side of gender-based violence, one that is rooted in macroeconomic policies, such as austerity measures. We set out the consequences of the fact that four out of every five governments are now locked into austerity measures, cutting public services such as health, education and social protection rather than pursuing wealth taxes and windfall taxes. In 2023, 120 countries are planning to further cut their social protection budgets as part of this austerity, despite the fact that the COVID-19 crisis has already cost women around the world at least $800 billion in lost income in 2020, equivalent to more than the combined GDP of 98 countries.

The pain of this coming austerity will, we show, fall more on women. And these cuts will be to services that are already inadequate. Our research shows that more than half of governments embarking on austerity already fail their women and girls, by failing to provide or barely providing gendered public and social services. These governments are, we argue, treating women and girls as expendable.

Why the Pain of Austerity is felt more heavily by Women

Austerity has a gendered impact: our report sets out how the pain of cutting social protection and public services is felt more heavily by women, girls and non-binary people because of the roles they play in the family, in society and in the work they do. For example:

Failing to provide publicly funded water and sanitation hurts women, as it is women who must then do most of the work of collecting water. Women and girls already spend some 200 million hours collecting most of the water used in their families.

In general, austerity measures lead to increased informal employment, which is likely to impact more women, who make up most of this sector. For example, in Africa, women make nearly 90% of the informal employment sector, where they are typically exposed to more unfair pay, exploitation and no pension, maternity or basic labour rights.

Cuts in child and elderly care services will increase the billion hours of unpaid care work women already shoulder per day.

Cutting wages in the public workforce, especially in sectors like health, hurts the women who represent 90% of that workforce, or education where they represent 64% of the workforce. Cutting jobs in these sectors will also therefore disproportionately impact job security for women.

Cuts in public transport spending hurt women more as, in most major cities, women rely on this more than men. In France, for instance, over two-thirds of passengers on transport networks are women and in Kenya, women are more likely than men to use public transport for household and care-related trips. Such cuts will also put women in more situations where they are unsafe and take away their freedom of movement.

Other common features of austerity, such as increases in value added tax (VAT) on basic goods and services, affect women who are often left with the responsibility of balancing household budgets and feeding their families.

The Feminist Alternative to Economic Violence

But such austerity cuts are not inevitable, governments do have a choice: they can continue to inflict economic violence on women by cutting public services, or they can spare women this pain and instead raise taxes on those who can afford it. A progressive wealth tax on the world’s millionaires and billionaires could raise almost $1 trillion more than governments are planning to save through cuts in 2023.

We set out in our report what we believe is a viable, feminist alternative to the economic violence of austerity. This includes

- Prioritising women and girls in budget designs. Just 2% of what governments spend on defence could end interpersonal gender-based violence in 132 countries.

- Ensuring women and non-binary people are at the heart of national budgeting and policy making to ensure they work for everyone, not just men.

- Funding women’s rights and grassroots women’s movements, especially in the Global South

- Investing in universal healthcare, child and elderly care, education, and protection.

- Generating accurate gender data and analyses to inform economic decisions.

Gender-based violence doesn’t only happen when women are physically assaulted: austerity – and the policies that rip away funding from the social fabric and systems that women and girls and non-binary people depend upon to survive and thrive – is systematic violence too. It is just as dangerous, just as universal and just as problematic for women and girls – leaving them vulnerable, impoverished and marginalised.

This year, during the 16 days of activism, we want to raise our voices with our partners across the world and show how writing economic policy can be an act of extraordinary violence, how gender-based violence is being inflicted as much by the pen as it is by the fist.