Nothing like a slightly drunken dinner table argument for getting the mental juices flowing. Most recently, I had a slight disagreement (memories a little vague) with a medic friend over child rights.

I started holding forth about some work I did in the 90s that totally changed my view of children (I was a relatively new father at the time). Save the Kids funded me to write Hidden Lives, a book on child rights in Latin America and the Caribbean, for which I travelled round the region talking and listening to children in a range of difficult circumstances – working kids, street kids, indigenous and rural kids etc.

The prism for understanding what I heard was the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of Child, which argues that children should be seen as having agency, voice and rights, which progressively expand from infancy to the age of majority (18). It is a genuinely radical document, which had led to a wave of child rights legislation across the region, but which has since rather been forgotten.

This was all very interesting for a new father, but even more so was the reading I did about the history of childhood. Two books in particular – Centuries of Childhood and Death Without Weeping, challenged my preconceptions, showing that contemporary Western notions of childhood as a ‘walled garden of innocence’ are a relatively recent historical construct, with significant differences across the world. In previous centuries, kids were expected to work and live like ‘mini-adults’, and no-one saw it as a problem.

When the book came out, I got into trouble for talking about what working children want (better rights, and a chance to go to school, but not to be chucked out of their work) or how street kids operate (building up networks of charities and others, and getting the best results from them – ‘the food’s better there but you have to pray all the time’). Trade unionists who saw child labour as an unmitigated evil objected to the first; street child charities to the second.

But I remained convinced that a rights-based approach, which values children’s opinion and agency, was preferable to we-know-best ‘adultism’.

Back to the stormy dinner. Sandra (not her real name) responded to this by saying ‘they would say that, wouldn’t they?’, arguing that abused children often protect their abusers, so it is the job of medical professionals like her to see through this and defend their real interests.

I reacted badly partly because I hate the phrase, which is so often the way elites/ custodians of expertise to discount the views of subordinate groups who refuse to conform to their view of what is good for them (Muslim women wanting to wear the veil; sex workers wanting better rights; excluded groups hating immigrants). Ignoring their views is both wrong in itself, and stops us learning about how the world really is, leaving us open to being taken by surprise when the people we thought we were supporting disagree with us, sometimes violently. She doubtless thought I was downplaying the need for protection of the vulnerable.

But digging in a bit more, Sandra was working within an entirely different framework of reference – a medical understanding of risk. As a retired paediatrician, she had spent decades seeing kids traumatized by the most awful forms of abuse, who were in genuine need of protection and help. And yes, that meant ignoring their expressed wishes because of the evidence of something much deeper and darker. Not much room in there for liberal notions of agency and voice.

And it’s true, confronted with the horrors faced by many kids, the rights-based discourse can seem rather superficial – it often ignores the deeper layers of psychology and human experience, where people go through traumas that largely disrupt their ability to ‘exert agency’. Not much use talking about ‘power within/with’ if people are in such a bad shape that they are too scared to leave their homes or manage their lives.

Obviously there is overlap. My wife has done brilliant work with groups of refugees who have suffered deep trauma in their home countries, building self confidence through group therapy and activities such as community gardening. But it seems to me that the development sector has a massive blind spot on psychology and trauma, and what that means for a rights-based approach, and Amartya Sen’s formulation of development as the progressive expansion of the ‘freedoms to be and to do’.

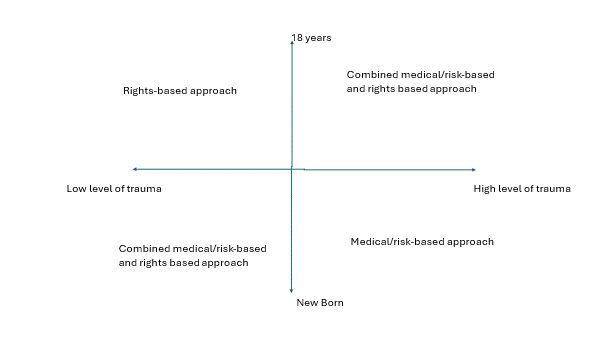

That involves marrying reconciling two very different ways of seeing the world, maybe even epistemic frameworks (yikes) – something that is always incredibly difficult to achieve. It’s a bit of a grim topic, but a 2×2 occurs to me. On the y axis is age, with children’s voice and agency rising as they approach 18. That’s the simplified rights-based approach. But Sandra’s experience suggests an additional axis, the with level of trauma. The best approach depends on the quadrant. Here’s a first go.

Can we bridge such deep disciplinary boundaries and have a joined up approach to both trauma and agency? Not sure – the divides are so deep that people barely recognize each other’s ideas. But it must be possible. If this is a bit garbled, I’m afraid that’s a faithful reflection of the conversation. And obviously, I’m likely to come out in a good light from my version of the discussion. But I’d be interested to hear what you think.

One could say it’s all rights based – the CRC does also lay out the principles of do no harm and best interest of the child combined with giving weight to child’s agency as they develop.

Author

Agree Harry, but the relative weight different professions/disciplines give to these differs widely.

Timely post Duncan. I was fascinated by recent work done by the IDS-led CLARISSA project in Bangladesh and Nepal. The importance of recognizing children’s agency in addressing the worst forms of child labor comes through very strongly. It is the children themselves who have blended a rights-based approach with practical protective interventions. They’ve even made a short movie on it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-stoGSX9No

Author

Thanks Shruti, will take a look

I am sure children have the right to safety and protection, and the agency is as much about ensuring they know how to protect themselves, and where to get support, in whatever context they find themselves in. This matrix is a useful way to think about agency and risk, but the lines are very blurred. In work I did as a learning facilitator with Comic Relief on ‘Girls and Gangs’, (In South Africa, the UK and Colombia) we had the two schools of thought amongst the grantees – those who worked with a harm reduction approach, and those who were working with a therapeutic approach. The harm reduction partners viewed joining a gang as a rational choice for many girls and young women – which is true – gangs can provide protection, income, access, housing and that exit should not necessarily be the end outcome. Yet, at the same time – these girls and young women are continuously traumatised by their associations with the gangs in various ways. Ultimately, what all the partners agreed on, was that anyone who is working with young girls in distressed communities has to adopt a trauma informed approach, as all the girls, even those where the work was preventative as they had not yet joined a gang, had already experienced trauma. Another issue that became centre focus, was inter-generational trauma – for example, in many communities there were multiple generations of unemployment. So all of the organisations were working in the top right hand quadrant. I think we would be hard pressed to find children in marginalised communities who have not experienced some level of trauma and are not exposed to daily risks of abuse, neglect or humiliation. We also know that post-traumatic stress disorder affects people’s ability to make good choices – so how does this influence the agency discussion. It’s a really really interesting debate and discussion, and one worth having. And then, even if someone does want to leave the streets, or a gang, there are so few options for them to do so. This highlights the critical role of prevention and early intervention work for children who are exposed to trauma and risk – but using a non-judgmental approach. We wrote a learning brief on it, which I can share if anyone is interested.

Author

This is great Dena, and takes the post into much more nuance and depth. Thanks!