Logan Cochrane and Alexandra Wilson on a fascinating new analysis that identifies four principles that drive NGOs to reject large donations – and if your organisation has turned away money recently, they want to hear from you…

Why would an NGO with a mission to provide high-quality health care reject donations of essential medicines? What would motivate an organisation to refuse tens of millions of dollars of food aid when over 700 million people are hungry? Why would a relatively small organisation refuse funding from the largest donor governments? These are real examples we have collected of NGOs refusing donations. We may have heard of such instances, but as far as we know no one has analysed the motivations behind such decisions.

In a world where 362 million people are in urgent need of humanitarian aid and nearly 700 million live in extreme poverty, it may seem unthinkable that NGOs would ever turn down funding. Yet, the reality is more complex. While the global demand for resources far exceeds supply, many NGOs, driven by deeply held values and humanitarian principles, sometimes make the difficult decision to refuse donations. These cases range from the very pragmatic, such as a public health organisation refusing funding from the tobacco industry, to refusals that take the form of activism.

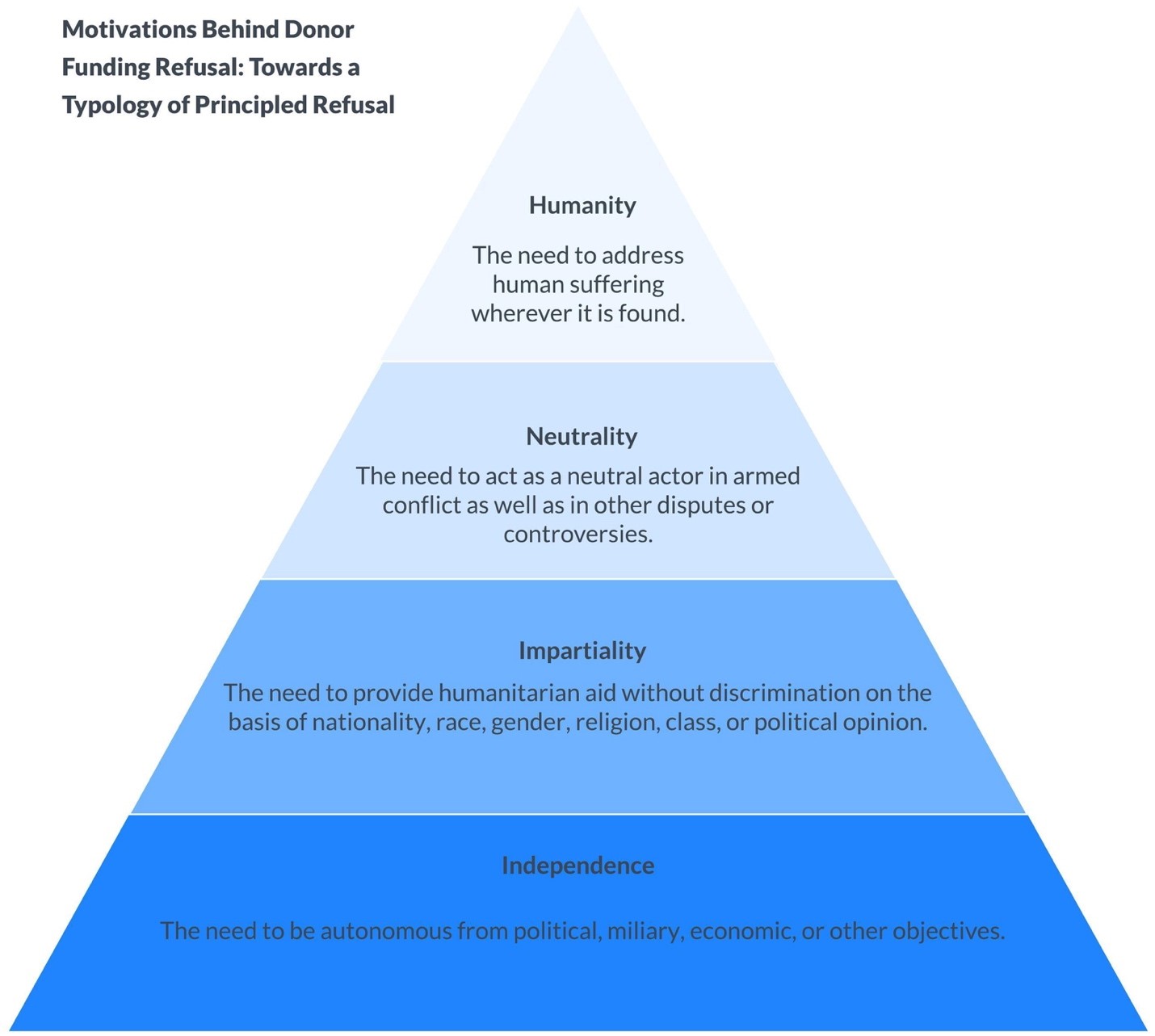

These refusals, however, are not well documented or widely discussed. In our recent study, Motivations Behind Donor Funding Refusal: Towards a Typology of Principled Refusal, we sought to address this gap by compiling a database of examples of NGOs refusing funding and identifying the key motivations behind these decisions, we found that these refusals are deeply rooted in maintaining key humanitarian principles – principles that are essential to the integrity and effectiveness of NGOs worldwide.

The Pyramid of Humanitarian Principles

Our research found that the decision to refuse donor funding is tied to the preservation of the four core humanitarian principles: independence, impartiality, neutrality, and humanity.

At the base of this pyramid of refusal is independence, the broadest and most common reason for donor refusal. Independence as a reason for refusal ensures that NGOs can operate without interference from political, military, or economic interests. This principle was made the foundational base to the pyramid as, without independence, the other humanitarian principles cannot be fully realised. For instance, NGOs such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch refuse government funding to maintain their ability to openly critique governments and their actions.

Building upon independence is impartiality. Impartiality as a reason for refusal is to help NGOs ensure that aid is provided without discrimination based on factors such as nationality, race, gender, religion, or political opinion. Refusals on the basis of impartiality also help to ensure that humanitarian assistance reaches those in need purely on the basis of need itself. One example from our paper is MSF International’s refusal of US government funding in 2004, after George W. Bush’s Foreign Aid in the National Interest policy imposed conditions on NGO funding, including giving the US government control over the NGO’s communications and staff recruitment

Next is neutrality. Neutrality requires NGOs to remain nonpartisan, especially in conflict zones. These forms of refusal often arise when affiliation with a donor could compromise the NGO’s ability to remain neutral in conflict areas. For example, NGOs such as CARE International opted to refuse funding linked to work with or alongside militaries in counter-insurgency efforts in Afghanistan as it would negatively impact their ability to uphold this principle.

Finally, at the top of the pyramid is the principle of humanity. Refusals on the basis of humanity work to ensure all humanitarian work is driven by a commitment to alleviate human suffering. Therefore, the reason humanity makes up the top of the pyramid is because humanity is the ultimate goal of any NGO, and maintaining independence, impartiality, and neutrality ensures that the principle of humanity is upheld. The most well-known case of collective activism by NGOs on the basis of this principle is the 1977 Nestlé boycott – launched by the Infant Formula Action Coalition (INFACT) after concerns about the marketing of infant formula in the Global South – which primarily targeted the Nestlé corporation. This led to some NGOs, such as Save the Children, rejecting all donations, monetary and in-kind, from formula companies.

A call to action: share your cases of donor refusal with us

Identifying the cases used in our study was difficult since no database of refusals exists. We want to address this, and make all cases available to everyone. For this, we have set up a mechanism to submit examples of refusal. We invite organisations and individuals to share their experiences. Whether you’ve turned down funding due to concerns over donor influence, political agendas, or ethical conflicts, your stories will help us better understand the complex dynamics of donor-NGO relationships.

So if you or your organisation have encountered a situation where you refused funding, we encourage you to contribute to our growing database. Your contributions will help illuminate the crucial role that ethical decision-making plays in the humanitarian sector. We will review and validate submissions for the database, and make those results available to everyone. This will enable learning about how we can collectively uphold humanitarian principles, including through refusals. We also hope this will enable and inspire new directions of research.

Logan Cochrane is an Associate Professor at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Qatar, in the College of Public Policy

Alexandra Wilson is a masters student at the University of Ottawa, Canada

“Motivations Behind Donor Funding Refusal: Towards a Typology of Principled Refusal”, by Logan Cochrane & Alexandra Wilson is published in the September issue of The Journal of Development Studies (open access)

Refusing donations is more common than is maybe thought. Here in Cambodia where corruption is such, with authoritarian authorities wanting to co-opt and control NGOs (both International and local), tainted money from ill-gotten gains is readily available. Next to that is where donors, having entered in to contracts with “partners” and given money apply conditionality to seek to influence them in their mission. That is much harder for NGOs to resist but the most honourable ones do.

Thank you John! We agree. Yet, not written about at all. We are hoping to enable a discussion about this topic and create an Open Access database for all to refer to. Please add your cases to the database! (see link above)

Curious how this idea might fit into the typology as it develops: What about donors just don’t offer useful capital? In my experience, decisions to say “no” to funding are often made on practical considerations rather than humanitarian principles. The opportunity costs of applying for, managing, and reporting via traditional grant mechanisms are just too damn high. When organizations are principled, they calculate that the amount of time spent servicing donor requirements (including information requests and whims) takes away necessary focus and precious energy from the problems at hand.

There are also other examples that I’m not sure fit, for example CARE’s move in the early 2010s away from USAID food monetization, various child-focused organisations’ move away from or restructuring of Child sponsorship, or decisions not to compete for funding to open space for local actors to receive it directly.

Than you Jennifer. Fully agree. We do not capture the pragmatic or operational (right terms?) forms of refusal based on donor administrative burden. However, could this fall under “Humanity” as a way to focus on the organizational work in a principled way?

This is really useful work, and I’d be keen to connect. There is a perception that NGOs, and INGOs in particular, just ‘go for growth’ but this often isn’t the case, though there are always trade-offs in how principles are applied. Where I think many organisations miss out is by failing to communicate these decisions clearly and the logic behind them, which means such decisions lose a lot of their power to reinforce legitimacy and establish credibility on the application of principles – particularly important at the moment when many of those trying to block effective aid from reaching people in need are proactively undermining the legitimacy of NGOs and other like the UN and Red Cross, not least via social media narratives and ‘foreign agent’ laws.

Please do connect Gareth. My email is on the database submission page.

Power dynamics allow funders to set the agenda and predetermine ‘success’, leaving no room for them to design their interventions or respond to changing contexts.

As history confirms, many times funds have failed to address the actual shortcomings.

ASAG, older women organization, is the only one that stood up to the wind, excluded from national and international funds.

Money doesn’t have to be a barrier. Knowledge, experience, guidance, and insight could help to identify promising solutions to turn a vision into reality.

ASAG there is more than achievement, look with courage!

‘Loss and damage’ in the poorest Albanian community: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSpcFXZHNBI