What is going on with the cuts to the UK’s aid budget? Judging from first impressions, the axe is being arbitrarily taken to a lot of really good aid programmes, with no overall plan or rationale. Surely that must be wrong – this is a £10 billion budget we’re talking about, even after the cuts. Any manager knows that budgets sometimes have to go down, but that can be managed well, or done badly. Turns out the UK aid system is firmly in group 2.

There have actually been two rounds of cuts. In July 2020, the government announced a £2.9bn cut based on what turns out to be an exaggerated estimate of falling GDP (if the economy shrinks, the aid budget stays at 0.7% of GNI, then aid has to shrink too). Then in November came the abandonment of 0.7% in favour of 0.5% – amounting to around £4bn in cuts.

We currently know more about the first set of cuts, thanks to a new report by ICAI, the independent aid watchdog, and it doesn’t look good. According to a summary in the Guardian, ‘UK civil servants were given five to seven working days to prepare 30% cuts. Ministers spent only seven hours discussing the proposed £2.9bn cuts to multilateral and bilateral aid, and then imposed them predominantly on the world’s poorest countries despite giving instructions for the opposite to happen.’

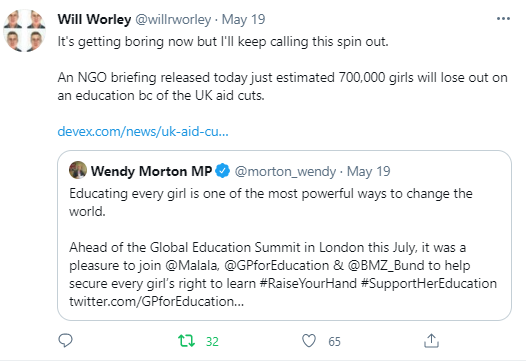

The latest round of cuts shows every sign of being just as chaotic and damaging, judging by a torrent of news stories about aid programmes and research being axed. Ministers have, to put it kindly, been on the back foot, defending the indefensible (or failing to). I’ve confirmed the general sense of chaos in a few off-the-record chats with colleagues at the FCDO, who seem very scared indeed of being accused of leaks like the one that embarrassed Dominic Raab in March (on the need to trade with human rights abusers).

Last week, Channel 4 News exposed one new aspect of the mess – ‘a plan to send surplus PPE to India was delayed as the Treasury insisted the items would have to count towards overall aid spending’.

£10bn is still a lot of money, and Ranil Dissayanake has done his best to piece together a picture of what kind of UK aid programme is emerging from the wreckage (since we’re not getting much help from the government in forming that picture).

Beyond the obvious damage to poor and vulnerable people around the world who suddenly lose access to food, shelter, family planning or other aid programmes, what is this kind of headline doing to the UK’s reputation?

This is a big year for UK diplomacy, chairing the G7 and hosting the climate change summit in Glasgow in November. At such moments, governments always like to be able to laud their leadership and build their ‘soft power’. That is very hard to do when all the press coverage is about the kind of miserly behaviour displayed by the Treasury towards India – the government is reportedly surprised by the level of negative press it is getting, but as one FCDO colleague put it ‘if you were trying to guarantee a long stream of really bad news, this is how you would do it – decisions at the top, then drip them out over time’. Boris Johnson is reporting to be having ‘queasy second thoughts’ at the diplomatic unforced error/shot in own foot.

The government faces a formidable adversary in Andrew Mitchell, DFID’s former boss, who is doing some devastating media interviews (example: the cuts will lead to a 100,000 preventable deaths, mainly among children) and whipping up opposition within the Tory party. Some pretty senior legal advice suggests the government ‘acted outside the law when it ditched its policy of spending 0.7% of national income on aid’.

I’m also hearing stories of just how much diplomatic damage is being caused at a national level. This from a colleague who works closely with UK aid programmes in a number of countries:

- Nigeria is probably less likely to want to cooperate with UK on countering violent extremism/terrorism or to strike a trade deal beneficial to UK after it feels the UK has abandoned it in terms of providing previously promised/pledged advisory support.

- It’s going to be a lot harder for the UK to claim a seat at the table in donor coordination efforts around humanitarian work in Syria and Palestine after such large cuts in both places, other donors won’t take such a ‘small player’ seriously – donor coordination in tricky places is something the UK prides itself on and is sometimes quite good at.

- The essential point is that anywhere there has been a big cut, it is going to be a lot harder for a UK Ambassador/High Commissioner to get meetings/favours/desired action from senior ministers in the country they are stationed in – UK diplomacy relies on that kind of influence and access.

Back in June 2020, Malcolm Chalmers argued presciently that the institutional loser from the merger might actually be UK diplomacy. That seems to be what is happening – partnerships damaged beyond repair, and ministers and MPs exposed to ridicule when they tweet about ‘global Britain’ and its latest initiatives.

What happens next? It’s not too late for the UK government to end the current diplomatic and moral train wreck. Firstly, a face-saving exit has become available – compared with the forecasts in the March Budget, the latest data and forecasts suggest that Finance Minister Rishi Sunak will have a lot more money than expected come the Autumn. That clears the way for the UK to say ‘hey, thanks to our great stewardship of the economy, we are able to restore 0.7’ – the obvious time for such an ‘announcable’ being the G7 summit in Cornwall next month. That could clear the way for a string of initiatives and announcements in the run up to Glasgow.

Wishful thinking or good politics (and the right thing to do)? Fingers crossed.