This new stream of resources that we’ll be posting on FP2P will include links to stories and projects that can engage us in further reflection about the many blindspots involved in development research and practice, as well as ideas to make those power shifts happen at every level.

Wellbeing seems to be something we all want, but like all things, even the most intuitively benign, it’s complex. And that is already quite an understatement!

Probably most of us who have ever set out to attain wellbeing at a personal level (with its immense range of connotations) have gotten frustrated at how slippery, time-bound, place-bound, and changing it is. And then there’s trying to attain wellbeing within our families, collectives, neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, and other life spaces we inhabit, with all their convoluted dynamics. So, when this scales up to trying to tackle wellbeing on a global level, an ambition familiar with the world of development, it gets mind-bendingly complex, real fast.

So here’s the sweet spot for our reflection this week: how do we incorporate wellbeing into our conversations, but ensure its radical potential as an idea is not diluted? How can we account for and value plurality in the politics of wellbeing?

Is wellbeing political?

You may have already heard the news, but in case you haven’t, two noteworthy things happened in the last two weeks which give impetus to this reflection:

- New Zealand’s Labour coalition government has unveiled a brand new “wellbeing budget”, prioritising addressing mental health, domestic violence and child poverty through its Living Standards Framework.

- The World Health Organisation has recognized ‘burn-out’ as a condition in the ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases), one of the main global health classifications.

These two moves point to a significant societal change, as ‘mental health’, wellbeing and affective limits become acknowledged as important considerations; even mainstream commentators such as financial journalist Martin Wolf are suggesting making mental health, equated with wellbeing, a basic metric for public policy.

It’s certainly exciting that such long-neglected topics are gaining more attention, and many positive ripples will emanate from these latest developments.

But in an age of abundant self-care mantras in the North and the individualization of “risk management” (read: care) everywhere, both of these moves throw up tricky questions: who is responsible for our individual and collective wellbeing? Is it ourselves? Our employers? The state? The market?

Secondly, how do we understand wellbeing, and what do we want wellbeing for? Many welcomed the WHO’s revelation, suggesting that the more we acknowledge types of excessive stress such as burn-out, “the more productivity rates will rise because people will be happy, and relationships will improve.”

Yes – we should absolutely acknowledge and deal with its consequences. But can anyone see the problem with the framing here? A first caveat is that labelling it as an “occupational” risk excludes those who fall outside of that perceived productive occupational sphere (aka those doing unpaid work = a lot of overloaded and overworked caretakers, parents, mainly women). And a second problem is, well, that it’s a systemic symptom – not an individual one. Here’s a Twitter thread that expands on this, posing the risks of depoliticizing sociopolitical conditions through medicalizing them:

Wellbeing is political, and thinking about it as such implies shifting resources, priorities and power dynamics. The ‘mental health’ frame, often at the bedrock of the wellbeing discourse, can indeed risk becoming an arena where we depoliticize social realities, pathologize issues and taxonomize conditions (based on very particular notions of ‘normality’). We’ll be exploring this particular conversation at a later time, but in the meantime, catch up on this recent blog on framing mental health as a development priority, and read the interesting comments it sparked.

Reframing the economy

The notion of wellbeing, in relation to development, is powerful because it poses a fundamental challenge to dominant understandings and metrics of prosperity. Placing wellbeing at the centre of our attention, disrupts an obsession with abstract figures – whether growth or gross domestic product (GDP) – as proxies of progress.

The notion of wellbeing, in relation to development, is powerful because it poses a fundamental challenge to dominant understandings and metrics of prosperity.

But as ‘wellbeing’ and ‘happiness’ begin to be increasingly adopted by states and enterprises as goals and frames of reference, it’s worth remembering that these ideas don’t come from nowhere, but from a rich tradition of heterodox economics. You might have already heard of Kate Raworth’s ‘doughnut economics’ model, which looks to ensure that human essentials are met within planetary boundaries, or about the ‘development at the human-scale’ advocated by Chilean ‘barefoot economist’ Manfred Max-Neef. Manfred Max-Neef in particularly spoke about fundamental human needs since the 80s, arguing that the supposed priority of economic growth was secondary to the importance of friendship, education, recreation, equal rights, and the ability to be creative.

Yet neither do these economic ideas and visions come from out of thin air, but rather off the back of feminist economics, Indigenous knowledges, and diverse worldviews and practices that point to a socially and ecologically just world. As wellbeing is increasingly popularized and institutionalized as a frame, how do we re-centre conversations around it? How can we think with the Global South on the topic of wellbeing?

Back to the Pluriverse

There are many powerful initiatives and voices in various corners of the world that have been crafting wellbeing as a broad concept which encapsulates both human and planetary wellbeing. A recently published book, Pluriverse, gathered over 100 examples of these practices and theorizations, including Buen Vivir in the Andean countries, kyosei in Japan, and prakritik swaraj in India.

Similarly, this new film launched by the ICCA Consortium, profiles multiple ‘territories of life’ across the world. From the Selkie community in Finland’s marshmires, to the Shahsevan Tribal Confederacy in Iran, the film shows the regenerative potential of communities prioritising their collective and environmental health.

Here are more videos, covering initiatives based in India from people-owned hospitals, to craft-based livelihoods, nature conservation, and others, which also point towards a concept of wellbeing that looks more like notions of localised justice. The Vikalp Sangam site offers many other stories of change and wellbeing as multifaceted, caring and justice-based concepts.

Centering Care

Moving away from just seeing wellbeing as a metric can be an invitation to shift practices toward ones underscored by an ethic of care. If wellbeing is our collective aim, it will inevitably involve shifting power dynamics (including resources) in order to center care – for each other, for our environment and for ourselves.

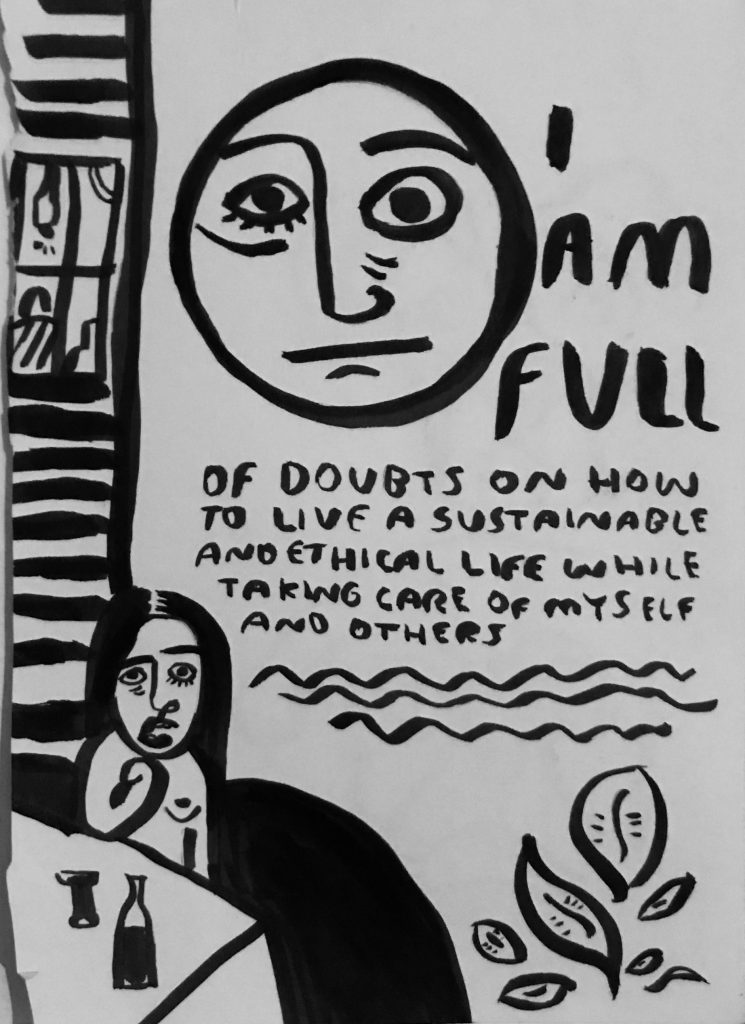

illustrated by Kruttika Susarla

Feminist collectives and organizations are paving paths in explicitly adopting ethics of care (and joy) within their spaces, in a way that inspires others to do the same. One example is the FRIDA fund, which recently released its own happiness manifesto as part of the process of dismantling exploitative structures, centering care and politicizing wellbeing.

The happiness manifesto goes well with this beautiful zine that emerged from a gathering of people working to prevent violence against women in the Global South, focusing on the role of self and collective care in the difficult work of tackling different forms of violence (more of their collaborative zines here). One important point in there is allocating necessary funds for support and other healing practices by “asking donors to finance care”. How do you think we can make this happen?

This is just the beginning of a conversation on care we’ll be continuing through #PowerShifts – watch this space for more, and feel free to suggest questions you want to explore through different resources.

And I’ll leave you with one question of my own: how are you centering wellbeing and care in your work?

Top featured image: “Coexistencia”, Areúz