The Adaptive Management discussion is dominated by donors, think tanks and academics, none of whom can really be described as ‘practitioners’. So I’ve learned a lot from working with Jane Lonsdale, one of the few exceptions. She’s an Exfamer turned big aid implementer, has run with AM work in Tanzania, Myanmar and now Papua New Guinea and is DT Global’s Adaptive Management Lead. Here she reflects on one of the many questions surrounding what has become quite a fashionable topic in aid circles.

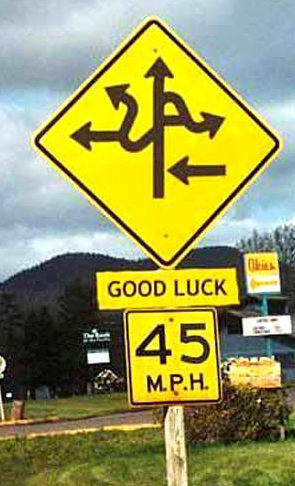

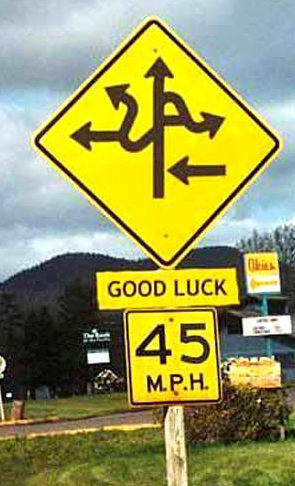

I’ve seen many situations where people are running around implementing lots of work without a plan or strategy and someone will excitedly exclaim ‘we’re being adaptive!’ Recent conversations prompted me to put down some thinking on how to differentiate what’s really going on in the management of a programme. When can we say this is good practice for adaptive management, and when is it actually just chaotic or bad management?

One defining feature of AM is the frequency of decision making and therefore adaptation at multiple levels, which is what I’ll focus on here. AM generally requires both slow and fast decision making on both strategy and particular activities. Often slow, planned adaptation of programme-level strategies, combined with faster, iterative adaptation of specific activities works as a basic framework.

There’s often more nuance to it than that of course. Depending on what’s happening in the context, slow or fast-paced adaptations may be needed at any time and at any level. When I ran an adaptive local governance program in Myanmar, we started thinking in terms of fast delivery cycles and slow strategy cycles. But things happen, often in Myanmar. Covid hit followed by a military coup 12 months later. We had to tear all our plans up and start again. Twice. For example, post-coup we had to ditch our insider advocacy with government and shift to advising on new civil society facilities instead. Exhausting stuff but luckily the program already had the systems to handle that quick strategy adaptation.

A basic guideline during a stable context period is that slow adaptation could be in a 6-12 monthly cycle. Fast adaptation could happen through anything from weekly to monthly decisions. Below I’ve set out what’s good and bad practice within these parameters:

| Slow adaptation | Fast adaptation | |

| Activities | AM: strategic patience – good judgement on potential for impact. BAM: Lazy management, decision avoidance. Low activity due to analysis paralysis (eg political economy analysis overload) | AM: responsive to environment. BAM: knee jerk reactions to donor whims, strategy drift. Too fast decisions- dropping potential high impact activity that requires strategic patience. |

| Overall Strategy | AM: Planned reflections, MEL leading to significant changes. BAM: Flexible chaos: no strategy, poor program quality, pet/orphan projects funded. Inflexible in responding to emerging opportunities. | AM: full program pivot response to major context change (major political change, war, natural disaster). BAM: knee jerk reactions to a poor review or a couple of failed pilots without proper analysis. |

Whilst this all sounds easy and performance measurable, the reality is that if you’re working on system changes it’s not possible to predict how the context will evolve. A fair amount of luck, accident and right place right time also comes into it. Which is why the concept of portfolio management or spreading your bets across a wide range of interventions is so important in adaptive management. So, in AM/BAM terms:

AM Initially investing small budgets in a whole range of interventions or partners. Seeing what is able to bring about change and therefore warrants larger investment and next level experimentation.

BAM: Investing too heavily in one or two unproven interventions upfront and for long time periods.

For example, in Tanzania through Chukua Hatua we tested a whole bunch of active citizenship ideas from training musicians on democracy, to Masaai radio slots on land rights. Then compared results using quick quarterly strategy reviews. We later went deeper with a couple of the most successful models.

A few more aspects of AM v BAM to finish on:

| Procurement | AM: Lighter, programme-specific procurement processes that are proportional to the financial risk involved across the program i.e. small grants → low requirements, big contracts → more due diligence. Ability to adapt requirements as necessary. BAM: Lack of due process in the interests of being flexible (programme quality goes out the window, potential for fraud increases). Or conversely, tightened processes in the interests of managing increased perceived risk* where a programme’s expected results are less known. |

| Monitoring | AM: clear account of what success looks like, what’s being tested, regular light touch data and ongoing light political economy analysis feeding into both fast and slow adaptation cycles. BAM: no/little monitoring (we’re adapting too fast to measure this), upfront major political economy analysis then little data on what’s changing in the context. Therefore, little basis for adaptations – likely to be reactive rather than responsive. And find it hard to demonstrate contribution/ impact. |

| Budgets | AM: good combination of short term planned and long term ringfenced funds, live budget updated at least monthly. BAM: large unplanned budgets with significant underspends and low activity spend. |

*Perceived risk- in my view traditional program management in complex situations and on sensitive issues is far riskier for impact than going the AM route.

Spotting where a program is managing adaptively, and when it’s just the bad kind dressed up as adaptive is a first step in correcting the course for improved impact. I’d be interested to hear your feedback on what distinguishes good AM and bad AM for you.

This is fantastic! Thanks for sharing. At UNDP we just designed/adopted a portfolio policy as a legal, programming & engagement instrument to partner with others on that is solely based on principles of dynamic management you outlined here… would love to connect & compare notes (lots of structural implications to this work for us once we move from not just calling things ‘adaptive’ or ‘dynamic’ but also doing them and lots of implications on our relationship with partners) because at least from what we’ve seen this isnt a minor hack but a pretty substantive u-turn on how decisions on dev funding get made.

Hi Millie, great to hear this was useful for you! Very happy to connect, I’ll drop you a message.

I am grappling with these different concepts (abbreviations?): AM and BAM. Does AM stand for Adaptive Management? And BAM for Bad Adaptive Management?

Author

Correct, apologies – my fault as the editor/headline monitor!

A nice set of examples, though thing that appears to be missing is the impact of communication.

I’ve been involved with projects where poor communication turns what could be good adaptive management into bad adaptive management as many stakeholders are unaware as to the nature and/or the rationale of changes, resulting in them unintentionally working at cross-purposes which generates an environment of mistrust.

This is true for internal as well as external communication.

Thanks Ben, good point on impact of good or bad communication. Agree it can make or break good intentions on AM.

Some more thoughts on the culture and ways of working needed for adaptive management in this guidance note https://dt-global.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/dt-global-guidance-note-introduction-to-adaptive-management.pdf

Also useful on this is the ‘3-blob’ conceptual framework by Angela Christie and Duncan Green which explains the trust needed at multiple levels for AM to work, blog on it here with the diagram:

https://frompoverty.oxfam.org.uk/what-have-we-learned-from-a-close-look-at-3-dfid-adaptive-management-programmes/

Thanks and catch up soon