Guest post by Jeff Hallock and Naomi Hossain

While the world was watching the war in Ukraine, its side-effects via rising food and energy prices were also playing out in the form of mass protests about the cost-of-living crisis in 148 countries. This global wave, unprecedented in world history, tells us that not only is the global economy in bad shape, but political accountability is similarly struggling.

In Sierra Leone, for example, by August 2022, food prices were so high that most people were spending most of their income on food alone. Protestors took to the streets, and one woman explained why:

‘One, we do not have freedom of speech, and two, there’s no respect for us, the women, and our economy is down, down, down, and the cost of living are very high. Because of it we’re suffering, we’re suffering.’

The government sent in the security forces, who fired indiscriminately into the crowds of desperate people. As many as 21 protestors and 6 police officers were killed in the violence, which President Bio branded ‘terrorism’.

The horrific events in Sierra Leone were just one episode among thousands in 2022. Cost-of-living protests are not mere glitches in the global economic machine: they are endemic failures of accountability. Loud and clear signals that global economic volatility is brewing political trouble worldwide.

International development agencies and actors do not usually cast themselves as players in such domestic political events. They rarely acknowledge that they bear some responsibility for these protests and how they are handled. But they should work to prevent violations of people’s basic rights, and track and draw attention to violent state responses. Above all, they should not make matters worse.

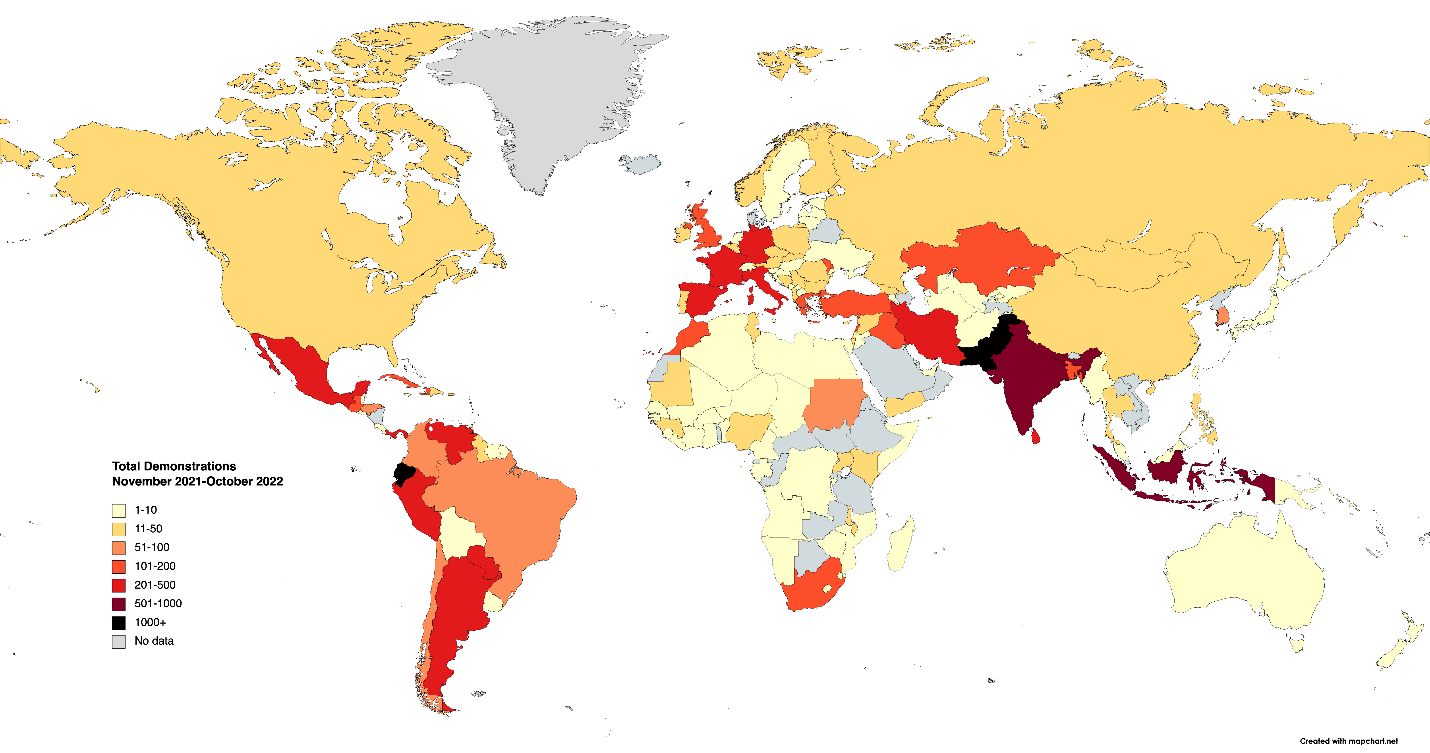

Figure 1. Global distribution of food, energy and cost of living protests, November 2021–October 2022

Source: Authors’ analysis of ACLED data

From November 2021-October 2022, the steep rise in food and in particular energy prices in the year since Russia invaded Ukraine triggered more than 12,500 protests across 148 countries about the cost of living (see Figure 1). Protests kicked off in all world regions, in democracies and authoritarian states, rich countries and poor. In 30 countries, there were at least 100 events; 13 of those 30 had or sought International Monetary Fund programs to get them through their macroeconomic crisis.

But people did not take to the streets just because they could not cope with inflation: many linked this failure to corruption and collusion between political and economic elites. Over and again people claimed that although it was risky, protest was their only way of being heard.

Analyzing the Armed Conflict and Location Event Database, we came to four conclusions about what these accountability struggles mean for international development.

- Protests are a risky way of defending basic rights. Cost of living protests are the point at which political and civic rights meet economic and social rights: people felt compelled to protest out of fear, desperation, and because they had no other way of being heard. But many governments are increasingly willing to silence them. There are good reasons why human rights defenders should specifically monitor violence against cost-of-living protestors, restrictions on such protests, and freedom of the media to report on them. If people cannot even protest acute economic crisis, they have no chance of holding their governments accountable.

- Failure to address protestors’ grievances breeds political mistrust and polarization. Governments that failed to act were seen as corrupt and unaccountable, and episodes of protest fed into political polarization, with far-right and left political groups mobilizing around popular discontent. This is why aid agencies pressing for economic reforms during crises need to do their risk and political economy analysis homework. If they do not want to contribute to deepening mistrust and polarization, they must consult citizens when they design policies, and be prepared with support for social protection systems to insulate citizens against price spikes and shortages.

- People are resisting unaccountable energy policies. Most 2022 protests were about energy, often featuring complaints that corruption and elite collusion were causing undue price rises. Energy policy-making takes place in exclusive spaces of extraordinary power, from which ordinary citizens and civic actors are barred. As Neil McCulloch’s new book Ending Fossil Fuel Subsidies shows, governments and multilateral agencies must involve citizens in energy policy reforms if they want them to work. Otherwise, transitions to renewable energy will be neither smooth nor just.

- Multilateral institutions have a responsibility to consult and engage citizens in their lending programs. Food and energy protests are often triggered by reforms implied by multilateral lending agreements. For instance, Ecuador’s 2022 protests followed events in 2019 and 2021 where citizens decried their government for being more responsive to the IMF than the needs of their people. Leonidas Iza, leader of the indigenous group CONAIE, which spearheaded the nationwide protest, stated that President Lasso was rigidly following IMF policies at the expense of Ecuadorians. Protests imply that multilaterals have failed in their responsibility to consult people in a meaningful way. Multilateral institutions bear some culpability for the violence and disruption that often ensues, and should monitor the outcomes of their preferred reforms. Data from protests should also be included in monitoring progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 16 in support of peace, justice, and strong institutions.

International development actors have long regarded cost-of-living protests such as the 2022 wave as the undesirable but trivial/short-lived side effects of necessary economic reforms. But it is more serious than that. When political accountability fails to the extent that people risk mass protests about the cost of living and the elite corruption that leave them unprotected and voiceless, international aid agencies are at least partly responsible.