Particularly liked the series of rather splendid blogs for International Women’s Day, written by our amazing LSE students. Here’s my favourite, not least because of the lovely blogging style: Does digitalised social protection worsen exclusion for women? by Divija Samria

Here’s the deal: digitisation of delivery mechanisms in public programs is increasingly being used to improve targeted approaches, reduce out-of-system leakages, and develop response channels in case of a crisis. And the best part? The simultaneous rise of cash transfers has provided ground for a unique opportunity to evaluate women’s empowerment beyond traditional means – by amplifying their voices within the household through financial independence. Sounds good, right?

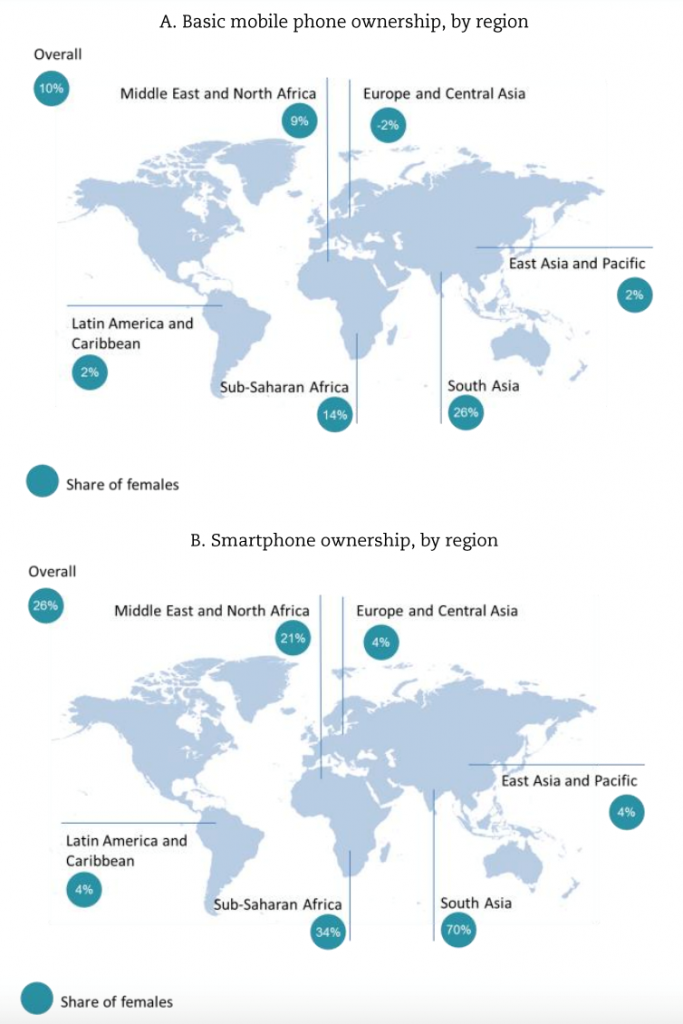

Digital access in the form of female ownership of mobile phones is only a precondition (or maybe pre-precondition) to digital use. It extends to other dimensions such as ownership of basic versus smartphone mobiles, adopting internet usage and specific uses for which these devices are employed. OECD (2018) reports that the gender gap in mobile ownership dramatically increases for smartphones in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (see below). Combined with the fact that male users are more likely to browse the internet, download and use apps, this implies that delivery channels with such needs are likely to (re)produce hurdles for women.

Now you are probably wondering, well, if not through phones or the internet, delivering transfer payments directly into women’s bank account could be an alternative. And rightly so, it indirectly addresses the above problems and simultaneously is a step in achieving financial inclusion for women.

The lag in digital literacy points to yet another flaw; female beneficiaries may still be dependent for spending decisions. Take the case of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) in India that opened bank accounts for under-resourced communities to directly receive transfer benefits, where 56% accounts were owned by women (as of 2022). The World Bank reports that although these accounts are being used actively to cash out benefit transfers, it has not resulted in the use of other digital financial services like savings, pensions or micro-loans. Similar results have been found with the M-Pesa initiative in Kenya. This suggests that the positive spillover effects expected from digitalized delivery may be limited for female recipients due to this gap between gaining digital access and acquiring digital knowledge.

Let’s take this a step further to look at the type of benefits transferred. There has been recent emphasis on cash transfer programmes with the aim of increasing women’s bargaining power at home. This could be either through payments that are unconditional or conditional on, say, improving school attendance rates or nutritional intake of children – the divisive initialism in development, CCTs (Conditional Cash Transfer). Two concerns emerge when cash transfers are digitally delivered: determining eligibility and undermining the role of mediated public service delivery.

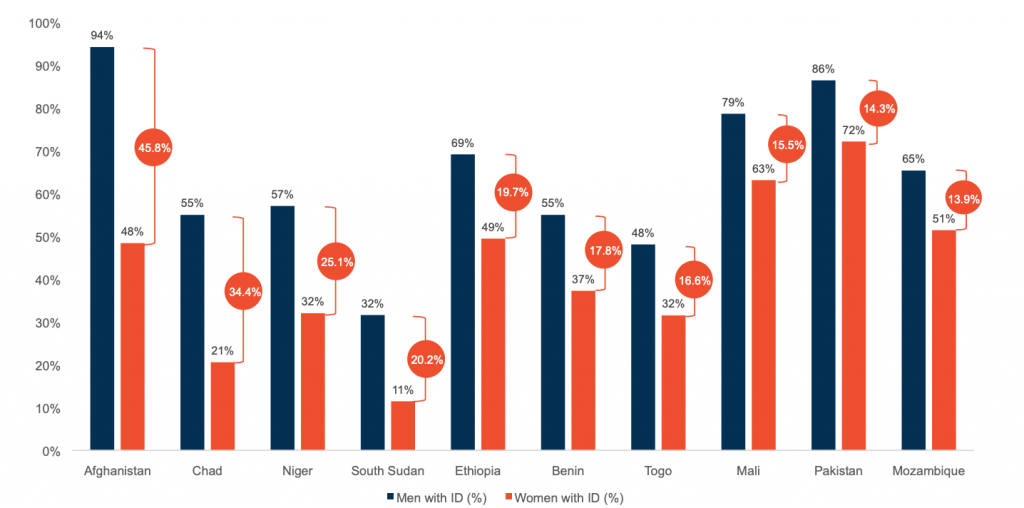

This way of public delivery, particularly to upscale social benefits, often relies on digital identity cards or automated screening to determine eligibility. A recent report by the World Bank (2019) highlights a gender gap in obtaining legally recognized digital identification (see below).

This gap is due to a combination of legal, economic, procedural, political and social barriers. It matters particularly in cases where statelessness becomes a key exclusion criterion. For instance, one of the report’s case studies’ quotes:

“I get pretty good grades,” says Patcharee (15), a stateless hill-tribe girl in Thailand. “Maybe I am even at the top of the class. But every time there is a scholarship, it is given to someone who has a national ID card.”

Sadly, there are concerns that these biases are reproduced in datasets made through algorithm-based technologies. For instance, a study from MIT (2018) that analysed 1,270 unique faces using a facial recognition software shows that darker-skinned females are most likely to be incorrectly classified, with the highest error rate of 34.7%.

Truth is, the old system of having frontline workers hand over these transfers directly have a participatory element. It allows space for workers to operate with nuance and discretion, develop relationships with beneficiaries and for caseworkers to provide interactive support. The need for networks and female kinships has been undermined in the process of ensuring fast-track online delivery. Gram et al (2019) point to this need to improve women’s agency in rural Nepal through an unconditional cash transfer intervention for pregnant women. As part of the experiment, a group of female facilitators transferred the unconditional benefit only towards the end of a group meeting that clearly communicated the purpose of these transfers. The study finds that when trained facilitators explicitly mention where the money is to be spent, both receiving beneficiaries and family members are more likely to spend it on the planned criteria. This evidence shows that manual service delivery possibly have an advantage in achieving intended outcomes for policies targeting women.

Professor Naila Kabeer’s view on ‘intersecting inequalities’ sums it up for us – digital exclusion is caused by other gender gaps and exacerbates it too. Digitalising channels through which welfare schemes are delivered may only result in short-term ease of delivery without addressing structural factors that have restricted empowerment of women. When viewed from this lens, ‘digital inclusion’ could be a social policy either in and of itself or interlinked with complementary programs to address gender gaps in digital access and literacy, and tech-driven targeting mechanisms. But this must be done after re-evaluating the strengths of traditional delivery models. Integrating the best of both worlds, as utopian as this may sound, offers the best hope.

See also Is the digital route a solution for navigating abortion bans in Latin America? by Freya Thompson, and The role of ICTs in perpetrating and addressing gender-based violence in Africa by Kolahta Asres Ioab and Nkechi Deborah Adeboye. Great work.