Changing power requires us to see the world differently. So as a final burst of energy to round up the lessons, insights and guiding lights from these two years of the Power Shifts project, we have set out to co-create a ‘virtual gallery for shifting power’. Through collaborating with two wonderful illustrators, we’ve attempted to find more creative ways to communicate ideas and transformative practices.

The following exhibit co-created with the Indian illustrator and artivist Vidushi Yadav, titled ‘Creating new horizons: paths to shift power and imagination in development’, displays a visual representation of some of the biggest debates surrounding ‘shifting the power’ in the development and aid sector. The original idea was to make graphic records of some of the main power-shifting debates, combining words and visuals to capture key ideas surrounding these. As seasoned graphic recorder Sonaksha Iyengar explains: “Graphic records help participants and facilitators bridge gaps between ideas and actions.”

These graphic records offer a window to think, see and feel the possibilities of radically better ways of working.

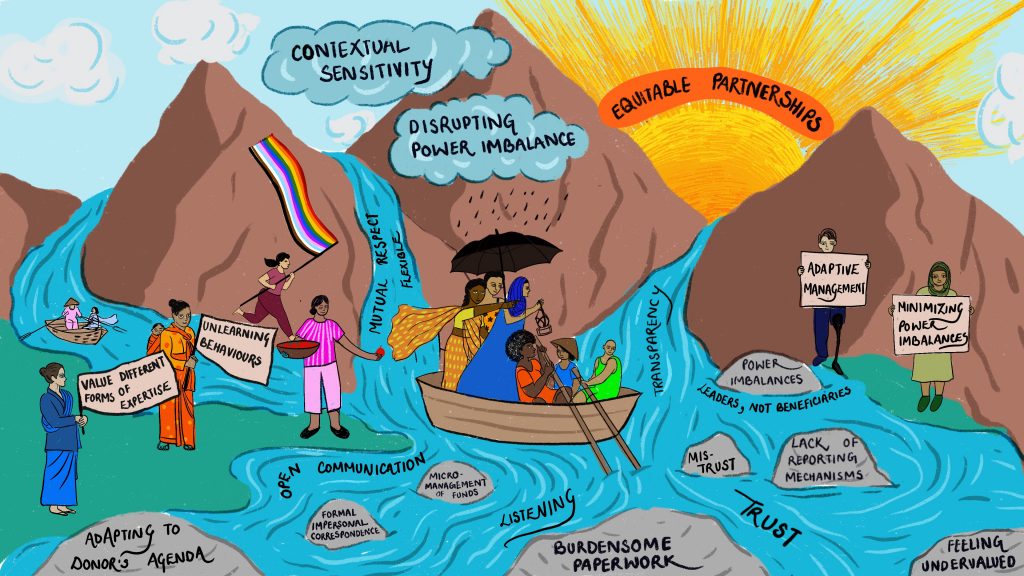

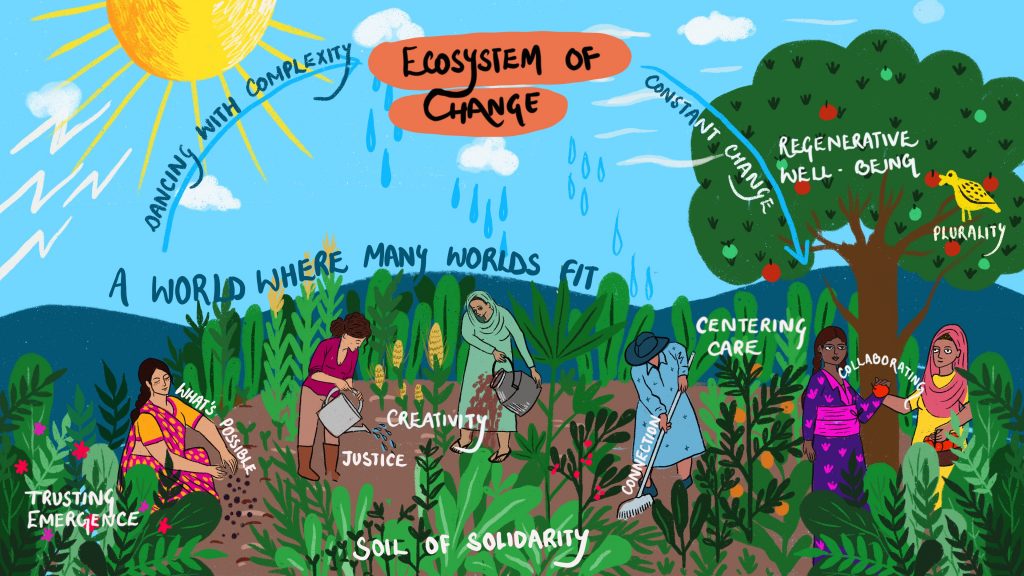

With Vidushi, we decided to explore more symbolic representations of each debate, hoping to visualize information using metaphors that many people can connect to. Rather than attempting to be exhaustive, and capture every detail of a debate, these graphic records offer a window to think, see and feel the possibilities of radically better ways of working. Each metaphor – a journey, a garden or a confluence of streams – visually explores five conversations around shifting power within the sector. Ideas, guiding principles and actions within each ‘shift’ are presented through symbols and words. These five ‘shifts’ correspond to those laid out in our first exhibit, ‘Development: a visual story of shifting power’, and each can be taken as a mosaic tile composing a wider landscape.

Below are the five debates we focused on, which overlap and necessarily impact one another. All are vastly rich ecosystems of thought and practice, and each merits an entire series of images. This is a small offering to begin, or continue, an exploration of what it could mean to engage in these power shifts. The images and visual narratives we have created can hopefully serve as a resource for fellow sector colleagues and provide inspiration for our power-shifting journeys. And just as a final reminder: these images follow two years of work on elevating critical voices and stories of justice through the Power Shifts project.

Like our other visual story, these images are published under a Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. So please go ahead and download, print and share them everywhere! Show them to your colleagues, plan a session to go through them together as a way to structure a conversation about ‘shifting power’, or dig deeper into one at a time with your teams.

Illustrations: Vidushi Yadav

Curation/writing: María Faciolince

1. Growing forests of knowledge

This process starts by questioning whose knowledge counts.This image invokes opening up the possibilities of knowing, which involves valuing, accessing and communicating a plurality of knowledges. Some of the main blockages to these shifts – represented by the toxic industrial fumes on the far right – include harmful narratives and concepts (such as ‘Developing vs Developed’ and those which perpetuate notions of white saviorism) , the tyranny of experts, the removal of politics out of social change, and relatedly, the dangerous insistence on offering technical solutions to socio-political issues. Many of these are encapsulated in what several critical voices have termed ‘the White Gaze’ of development.

Opening up our ways of knowing means confronting this gaze and its role in the enduring effects of colonialism, and making space for diverse forms of understanding around what it is to ‘live well’. Such endeavours necessarily mean elevating other forms of expertise – e.g. lived experience – and Indigenous worldviews and practices, unpacking power dynamics – including those in research – that continue to limit the possibilities of collective well-being, and making it possible for everyone to reclaim their own representation. If we’re still talking about knowledge production systems, it inevitably involves making information accessible to all. But ultimately, like this image illustrates, the horizon is to move towards growing knowledge collaboratively, cultivating it in processes of mutual learning and cross-pollinating abundant knowledges to strengthen local actions.

2. Bridging gaps to shake up our organizational cultures

Redefining development also requires shaking up our working cultures to build collective power rather than hierarchical structures, to commit to anti-racism and feminist leadership, and to center care in our organizations. These bold transformations require a reckoning with historical trajectories that feed into our work, especially legacies of colonialism that manifest in the systemic racism underlying thought and practice in the sector. They demand combatting the silences surrounding these legacies and recognizing how they shape present-day cultures and practices: from hiring protocols, to ways of working, to how strategic roles remain dominated by certain demographics.

The guiding principle for this work, underscored by several of our Power Shifts contributors, is building an ethic of care: centering care in how we relate, work, think and act. Actions that are necessary for this bridging work are illustrated as boxes being passed and carried over in collaborative ways, from accountability to access, from challenging decision-making to taking commitments to change seriously.

3. The journey of establishing equitable partnerships

With social movements, local collectives and young people as protagonists of systemic change, understanding how to equitably partner with and enhance the power of their leadership is a priority. Establishing horizontal collaborations goes beyond improving interactions: it requires a radical rethink of how international organizations operate. Some important obstacles that many have identified – represented in some of the rocks that obstruct the flow of the water in the image – involve lack of transparency and mistrust, adapting everything to donors’ agendas (limiting creativity, flexibility and the possibilities of co-creation), the draining bureaucracies involved in obtaining and establishing partnerships, and both explicit and subtle power imbalances that come across in behaviors such as micro-managing and over-editing.

On the shorelines, diverse people hold up placards, which represent signposts to guide this journey: valuing different forms of expertise, actively working to minimize power imbalances through collaborative practices and valuing the care work to build relationships between accomplices, rather than transactions across ‘funders’ and ‘beneficiaries’. In this journey, contextual sensitivity is paramount, as is making sure there are channels for transparent and open communication that allows for mutual respect to sustain the relationship.

4. Redirecting the flow and destination of resources

Power shifts are inconceivable without a redistribution of resources. Yet redistributing resources is not simply a case of changing who the money goes to, but how resources flow. Many local grassroots organisations are currently limited by dominant funding cultures in the development space. Often, under the surface of sorely-needed funds, small-scale movements will face a series of exhausting requirements, taxing procedures, and risk-averse donor agendas. New approaches, such as community philanthropy, are showing how funds can flow more flexibly, transparently, and effectively in communities. There are of course tightropes to be balanced with safeguarding and legal requirements, but shifting the lenses through which we see the flow of resources and funding can help us move from charity to solidarity, from plans to emergence.

5. Valuing ecosystems of change

The development sector can only grapple with the compound crises of our time by being as sophisticated as the systems we’re trying to shake up. This approach invites us to think in systems, and work at the intersections, where social issues collide and interact. As black feminist writer Audre Lorde reminds us, ‘There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.’

A systems approach forces us away from the comfort of strict categories and linear analysis, and allows us to work with complexity, rather than denying it. It encourages us to dive into the work of intersectionality and silo-smashing, placing greater faith in playful processes and emergence, over ‘perfect’ plans and blueprints. As Vidushi’s image shows, a systems approach is abundantly fertile; when we dance with complexity, and admit that what surrounds us is a deeply intricate and constantly evolving pluriverse, we can sow seeds of immense possibility, creativity, and regeneration. Through these lenses, we can draw new horizon lines of collective well-being, weaving a world where many worlds fit.