I’m a big fan of league tables for comparing performance by powerful players, whether governments, NGOs or corporates. If done well, they can prompt a race to the top, with players competing to move up the table in successive years. The latest one of these to cross my timeline was the 2023 Food and Beverage Benchmark Report, produced by ‘KnowTheChain’, a programme of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, which is run by my old boss Phil Bloomer.

It’s an ambitious exercise:

‘KnowTheChain’s 2023 revised methodology prioritises policy and process implementation in assessing whether companies’ actions to address forced labour risks in their supply chains result in meaningful improvements for workers.

While most companies demonstrate policy commitments to address forced labour in their supply chains, they consistently overlook the power of preventative measures including supporting freedom of association and access to effective grievances mechanisms. This, coupled with a lack of evidence on remedy outcomes for workers, signals the existence of policies alone is insufficient to materially address forced labour risks and improve outcomes for workers.

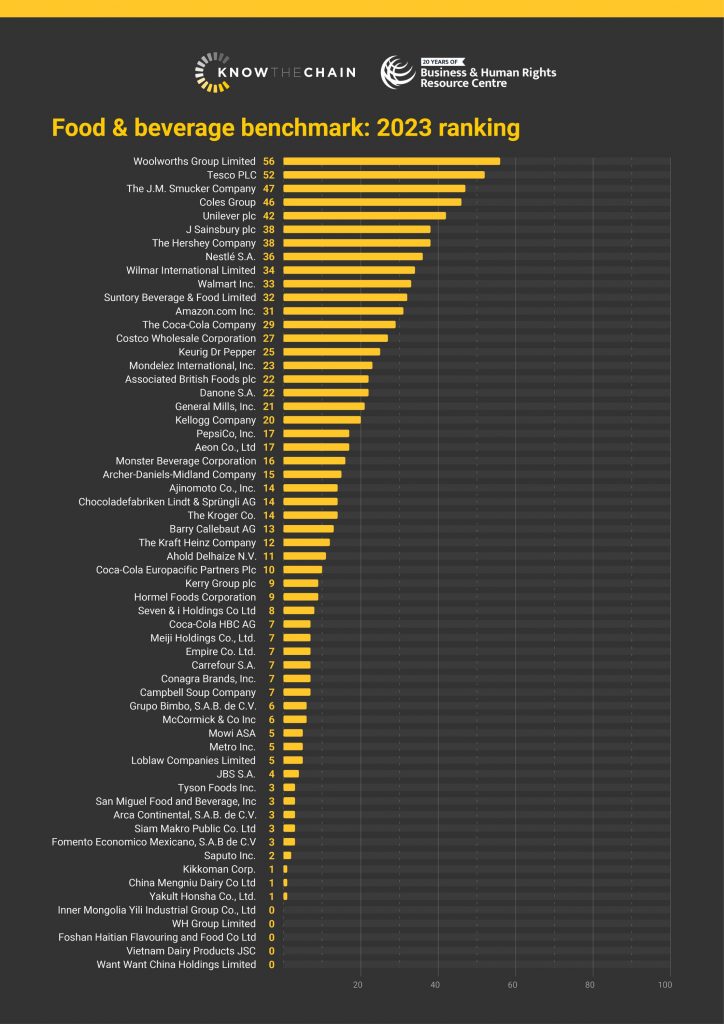

To this end, only half of companies assessed score more than 10/100. Five companies provided no relevant information whatsoever on how they were addressing forced labour in their supply chains: Foshan Haitian (China’s largest soy sauce manufacturer), Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group (Asia’s largest dairy company), Vietnam Dairy Products (Vietnam’s largest dairy company), Want Want China Holdings Limited (China-based packaged foods company), and WH Group Limited (the world’s largest pork producer).

Generally low sector scores, combined with a lack of transparency by such significant market players, should be cause for alarm for companies and their investors.

The gap between the lowest and highest scoring companies within the benchmark is also significant. While there is still room to improve, Woolworths Group (56/100) and Tesco (52/100) provide examples of better practice in addressing forced labour risks within the sector, posting particularly stronger scores on key themes such as Recruitment. Others in the benchmark have no excuse for not following this lead.’

OK, but a big elephant in the room went unmentioned in the report, as far as I could see. Look at that list of bad guys and good guys, or the full table. Notice anything? Every one of the bad guys is a developing country multinational (WH Group is Chinese). The good guys are all from the global North.

Why could that be? 3 possible (slightly overlapping) explanations come to mind:

- Southern TNCs are less susceptible to public campaigns, either because they are less dependent on their brand, or less likely to have shareholders (because they’re family owned), or because public opinion in their home countries is not as strong on these issues as in the North.

- Southern TNCs have a different conception of corporate responsibility from what is being measured here.

- Southern TNCs stick more firmly to Milton Friedman’s dictum that ‘the business of business is business’, and just don’t care.

I was sorry that the report didn’t dig into this – clearly, if we want to generate a race to the top, and half the runners don’t even consider themselves part of the race, we have to do more to understand what is going on, and adapt tactics and narratives, and what is being measured, accordingly.

I sent a draft of this post over to Phil and got some interesting responses. Surprise, surprise, turns out things are a bit more complicated than I first thought:

‘In global supply chains, some of the worst performers are suppliers to some of the better performing companies (ah, the complexity of long supply chains and their ability/design to allow abusive conditions for those at the bottom!). You can see this clearly in our Know the Chain report on phone and computer manufacture. In many sectors it is not a simple South-North divide. Canadian mining companies, and Japanese companies can often be poor performers, for instance. And the irresponsible purchasing practices of many US and European brands drive abusive practice by suppliers – this was turbo-charged in the pandemic.

We would generally agree with the possible reasons you highlight for regional differences. But we’d advise against making major distinctions between those that score zero and those that score 10% – the impact of such dire scores for those caught in forced labour is likely the same. And in this larger group there are some big western brands and companies.

Two other short remarks:

- The benchmarks do, as you say, help to generate a race to the top (and an observable race in the ‘catch-up group’); but many of the laggards appear unmoved by the opprobrium of their score. This leads to the second point:

- Perhaps the most useful contribution of human rights benchmarks has been to provide governments of good faith with the evidence that their 40 years of reliance on the neo-liberal precept that they can depend on companies’ voluntary action, combined with a little ‘nudge politics’ (a la UK Modern Slavery Act) has been ineffective and a fig leaf for the sustained toleration of abuse of workers and communities in supply chains. I don’t want to overclaim for benchmarks – it takes a whole movement to gain the current seismic shift to human rights and environmental due diligence regulation in Europe. But benchmarks’ evidence has been used systematically (by us and others) to demonstrate to interested governments the need for effective regulation to raise the minimum floor of corporate behaviour. It is also useful to counter the claims and lobby of reactionary business associations that there is no need for the inclusion of civil liability and heavy penalties for violation in this regulation because they have it all in hand through their sectoral voluntary schemes. Clearly not.’

Thanks Phil, and over to the readers/other practitioners to comment