Guest post by David Martin and Yogesh Ghore

What can you achieve with C$30m and none of the usual constraints faced by official donors and NGOs? That’s the challenge for so called ‘venture philanthropists’ like us. The Comart Foundation is a mid-sized, family-run, Canadian charitable foundation, with an endowment of C$30 million and no permanent staff. From our inception in 2000 we saw our mission as investing in grassroots initiatives, particularly in agriculture in Africa. We wanted to learn what works in the real world.

We were willing to invest in “high risk/high reward” initiatives without pre-determined outcomes. We were quite prepared to “duck and weave” during the course of a project in the face of unexpected problems and opportunities. If the result was a viable concept, we hoped that bigger, more risk-averse funders who did want predictable results from a proven model would then jump in.

Asset Based Community Development

We had already made an investment with ILRI in East Africa and were aware of the frustration experienced by research institutions because farmers were not just spontaneously picking up the nifty technologies they were putting on their doorsteps. From what we’d seen we thought ABCD might help. We saw that ABCD farmers who had gone through the ABCD process were motivated to see their land and their farming skills as an asset to help them out of poverty. As one Ethiopian farmer told us: “More important than changing how a farmer does things is changing the mind of the farmer—that is what is happening here and what you will see.” This “change of mind” was coming to see farming as a business.

Building an ABCD accompaniment process

With Coady we put together a five year plan for exploring ways to build up ABCD as an accompaniment process, helping communities through alliances with agricultural research institutions like ILRI and ICRAF.

This worked very well, but towards the end of the five years we discovered a serious flaw in the model. Communities had, perhaps inevitably, focused on the supply side, rather than the demand (market) side. The most dramatic illustration of this was the story of an ambitious ABCD community in Ethiopia that decided to build on their success by getting into dairy. They brilliantly organized the supply side. They organized a 100+ member co-op, purchased chilling and quality control equipment, set up para-vet support, underwent all the appropriate training – and then found they couldn’t sell their milk. They hadn’t done the necessary market research. It was heart-breaking.

Farming as a Business: Getting the Numbers

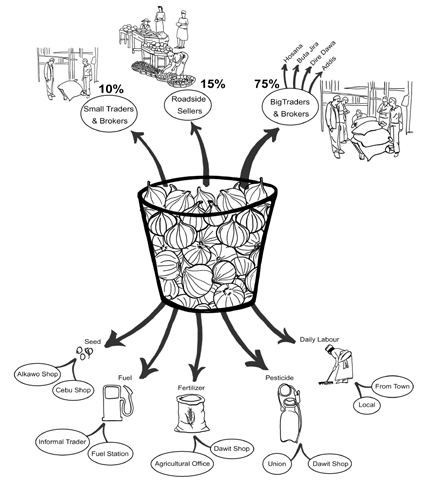

In response, in 2012, Coady’s Yogesh Ghore created the Producer Led Value Chain (“PLVC”) model. This involved farmers visiting local markets and establishing market prices, quantity and quality requirements, and doing a similar exercise for their farm inputs. They then used these numbers, the product of their own hands-on research, to create a budget for an average farm to establish the profitability (or not – often not) for a given product.

The results were illuminating. As one Ethiopian farmer said, “Before ABCD we didn’t realize the resources we had; before [PLVC] we didn’t know which businesses were profitable and which were not. This has helped us choose and plan… We have been sleeping. We didn’t realize what we had.”

We were obviously on to something. For the past ten years we have been working with smallholder farmers (women and men) in Kenya, Ethiopia and India to build up a robust PLVC/ABCD model that delivers results for them. We were happy to find that most farmers were quite capable of dealing with numbers and record-keeping. They started budgeting for their farm activities, keeping records of their actual revenues and expenses and then comparing them to the original budget.

We now have hundreds of farmers keeping careful business records with those of the farm (or other business) separate from household records. These numbers are very credible because they are used by farmers to drive their own business, so they have every incentive to make them accurate. We’re engaged with ICRAF in aggregating these numbers for analysis and for feedback to the farmers.

Lessons Learned

ABCD works and is a powerful catalyst for change. It creates agency, builds assets and wealth and, above all, dignity. The community chooses its priorities and drives its own development; outside experts and NGOs are “on tap” and not “on top”.

Venture Philanthropy works. We have leveraged significant investment from others.

A big difficulty is finding NGO partners for communities that respect this fundamental paradigm shift. The typical NGO is used to a top down, needs-based approach and usually has a particular approach/product it wants to see adopted (whether the community shares its priorities or not).

Another difficulty yet to be addressed (except in the case of SEWA in India and WISE in Ethiopia) is sustainability. To date the ABCD accompaniment process has relied on a benevolent outsider like ICRAF who understands and respects the process and can act as a “linker” to outside resources. Ideally communities, or groups of communities, would set up structures – co-ops or unions – to fulfill this linker role.

Our gut instinct is that incorporating the ABCD approach should produce superior results for development actors. But do the actual numbers now being collected from farmers confirm this? We look forward to finding out this year.