Guest post by Hannah Ryder, CEO of Development Reimagined, and former head of partnerships for UNDP China

What do the governments of countries like Cameroon or Cambodia really think of Chinese aid and loans? It’s a question few commentators and funders ask, and even fewer are interested in helping respond to the challenges they raise.

Instead, the focus is typically on how North American or European governments view the Chinese government’s aid for poorer countries – from accusations of “debt traps” to “donation diplomacy”, while the audience for most work on China’s international footprint is typically North American or European interlocutors.

Two new papers by analysts at Development Reimagined, an African-owned development consultancy headquartered in China of which I am the director, published by the Center for Global Development, a Washington- and London-based think tank, represent a first step in addressing this deficit.

The first paper – China’s Aid from the Bottom Up: Recipient Country’s Reporting on Chinese Development Cooperation Flows – interrogates a set of fascinating data sent by recipient countries such as Cameroon and Cambodia every 2 years to the Global Partnership for Development Cooperation (GPEDC), which was created in 2011. It is the only data set that sheds light on how effective China’s aid for developing countries is, both across those countries and compared to other aid providers, from the recipients’ perspective.

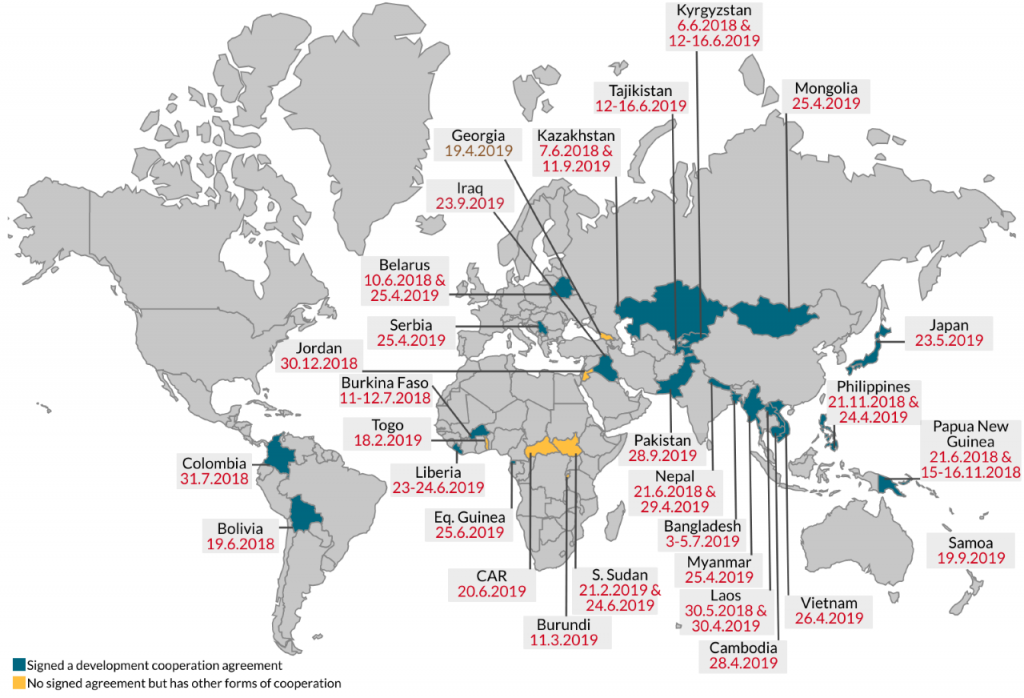

The most recent round of data collated by the GPEDC includes data on China coming directly from 27 very different countries across the globe, covering approx. $1.2bn of Chinese aid in 2017, and a mix of loans and grants. The paper also digs deeper by providing the results of interviews and a survey to understand why and how the recipient countries gathered the data and the challenges they faced.

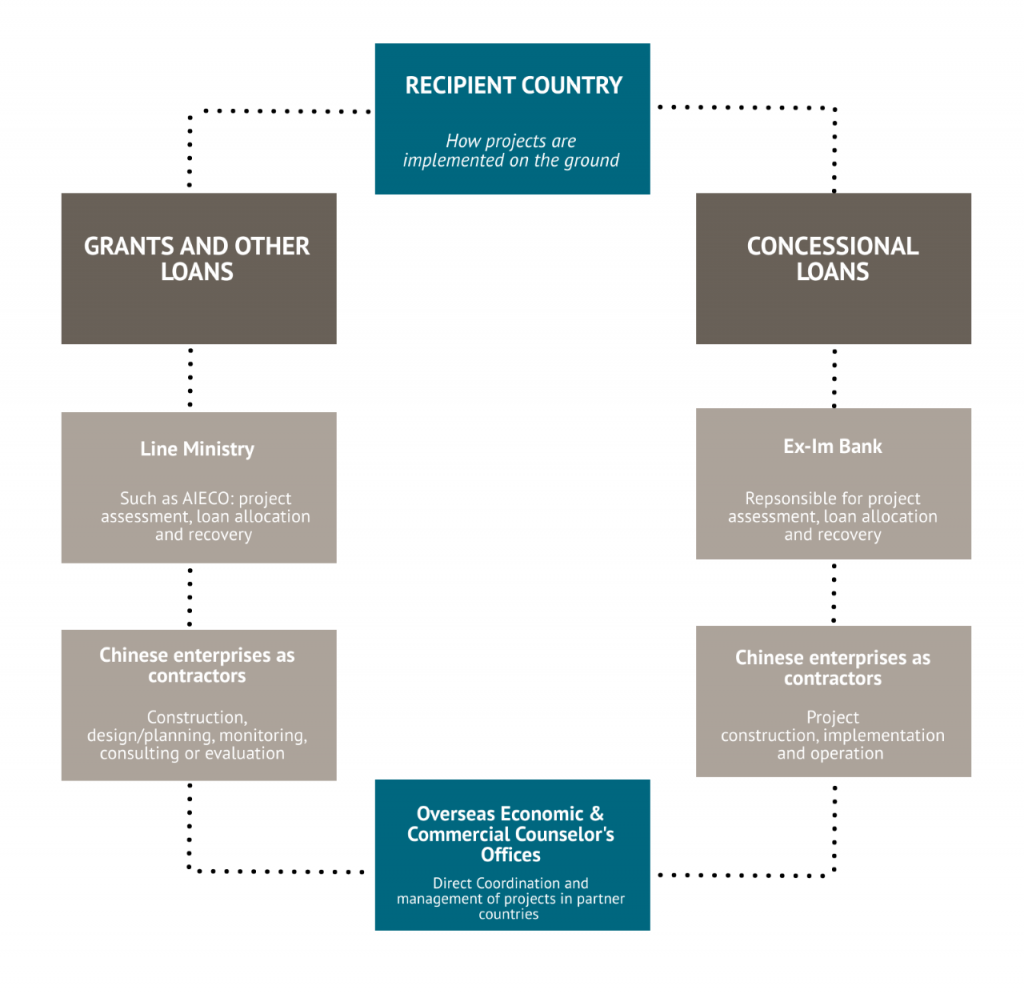

The second paper provides a “beginner’s guide” to China’s foreign aid. With helpful diagrams, the guide is written with government representatives and civil society in recipient countries in mind, so that they can better understand the systems and use this understanding to demand what they need in the way they need it from China, as China did itself with its aid partners, and also push others development partners to do better, based on the best of Chinese processes.

So what does the report say that governments such as Madagascar or Nepal want to change about Chinese aid to ensure it reaches the poorest people?

First, the good. In the eyes of the 27 reporting countries, China performs well on compared to other aid providers on aspects such as how predictable the aid is – i.e. usually if Chinese stakeholders say they will deliver a project they will – and also how much the aid can be transparently recorded on government budgets – reflecting the fact that Chinese aid is often negotiated between governments, rather than channelled to the private sector or civil society, which is more common with other development partners.

The bad? The 27 reporting countries suggest that China seems to be more focused on inputs (e.g. roads built or health kits donated) than real results in terms of poverty reduction, and many of the ideas and delivery of Chinese aid come from and are by Chinese stakeholders – not the country’s own (i.e. tied aid, in the jargon). Most also feel that China’s loan and grants procedures are complex, even just for recording purposes.

Overall, the data and responses from recipient countries show that neither China nor other aid providers can claim to be unequivocally better – they all have a way to go to fulfil modern expectations for truly beneficial development partnerships.

And that’s the real challenge. China is just one partner in a global aid industry that remains ineffective.

Jonathan Glennie, Lead Author of the report, said: In giving aid, China should not be accountable to the Global North. It should be accountable to the Global South and the key issues the Global South cares about. Our report shows that recipient countries desperately want to understand and manage aid themselves, whether from China, US or the UAE. The role of the international development community is to amplify and support this desire and help aid recipients gain more agency vis-à-vis China as well as other development partners”.

That’s where the “guide” comes in – it responds directly to this challenge by clearly setting out Chinese aid management structures to help recipient countries better engage with their Chinese interlocutors, and get the best out of Chinese aid, however “good” or “bad” it currently is.